Press play to listen to this article

Voiced by artificial intelligence.

LONDON ― British banks fear the politicians are gunning for them. The politicians say they’re not. Who to believe?

Even as Italy last week offered a blueprint for how NOT to impose a windfall tax on banks (announce it unexpectedly, be hit by a massive sell-off of stocks, backtrack 24 hours later), the financial sector knows that for as long as they’re racking up profits, creaming some of them off to boost state coffers always will be a temptation.

And in the City of London, with a general election looming, banks are getting jittery.

After all, how better to convince ordinary voters you’re on their side during the most severe cost-of-living crisis in a generation than by hammering the money men? And what better time to do it than when U.K. banks are making huge amounts of cash?

In a revelation that surprises no one, the banks hate the idea. “It would simply make the U.K. even more uncompetitive relative to other international financial centers and therefore less attractive for businesses and investors,” said Helen White, head of policy at the TheCityUK, a lobby group for the industry.

And they don’t necessarily believe politicians when they say they’re not plotting something. Of the two main political parties, City insiders say they fear Labour, which is significantly ahead in the polls, is the more likely to try to get their hands on their earnings.

Charm offensive

A banking windfall tax could raise between £5 billion and £20 billion this year, according to Positive Money, which campaigns for a fairer banking system. For the more populist-minded politicians, it’s a sum that’s enticing as the election ― due by January 24, 2025 but expected some months earlier ― gets nearer.

While in public at least, Labour has been busy telling the City to relax, behind the scenes there’s nervousness that if and when he gets into Number 10, its leader, Keir Starmer, could be ready to pounce, especially as households struggle with higher mortgage payments.

“It wouldn’t seem entirely outlandish to expect there to be at least a Labour internal debate about how to fund any mortgage holiday scheme, should it be put in place,” said one bank lobbyist who was granted anonymity to speak freely.

It’s certainly not current Labour policy. In fact, in a long-running charm offensive, the party’s top brass — including Starmer, Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves, Shadow Energy Secretary Jonathan Reynolds, Shadow Chief Secretary to the Treasury Pat McFadden and Shadow City Minister Tulip Siddiq — have been pounding the streets of the Square Mile to reassure financiers that they are pro-business centrists rather than left-wing radicals.

“I’m not convinced by the evidence for a windfall tax on the banks. What I do want to see is all banks, all lenders, doing the right thing by their customers,” Reeves said in a television interview at the end of July.

It’s a similar story with the Conservatives, who have been in power for 13 years. While the rhetoric to voters has been about bashing the banks — hauling CEOs into the Treasury over savings rates and mortgages and to discuss Brexit Party founder Nigel Farage losing his account over his political views — there’s no indication they’ll go after them in any meaningful way.

“We already have two specific taxes for the banking sector – the bank levy and the bank corporation tax surcharge – and the entire U.K. banking sector generated around £39 billion in tax last year which is almost enough to fund the entire police and justice system,” said a Treasury spokesperson. “The Chancellor has been clear however that banks must pass on the interest rate increases to savers so they can benefit.”

Foot shooting

Still, there are shades of gray which would be less extreme than a full-on Italy-style windfall tax. One option banks fear is an increase in the surcharge on their profits. This, dating from just after the global financial crisis, was lowered to 3 percent from 8 percent by Chancellor Jeremy Hunt in November to counteract a rise in corporation tax, but it could easily be hiked up again.

Any further raid on bank profits could spook global firms that are less wedded to London after Britain’s departure from the EU.

“If they really put the boot into the City and jump up taxes, Labour would be shooting themselves in the foot economically,” said Michael McKee, a senior City lawyer who heads up DLA Piper’s European financial services regulatory practice.

“What happens if you increase the tax burden? The consequence of Brexit ultimately for the moment has been to make the U.K. less attractive rather than more attractive for financial services businesses.”

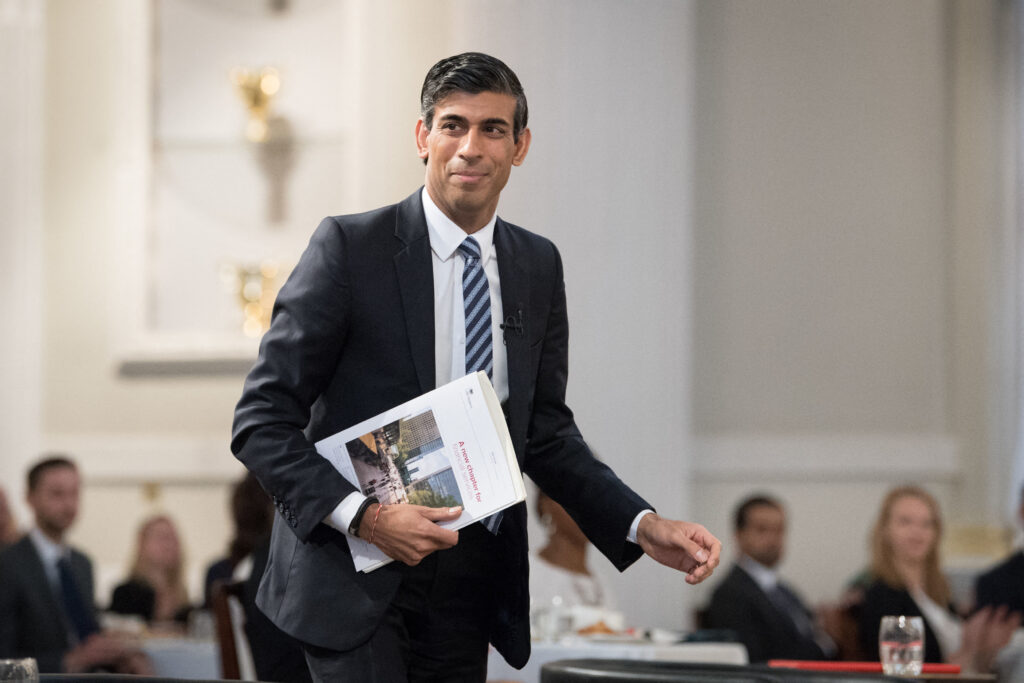

Stable Sunak

And it’s Brexit that hangs over this entire debate. The City took a hit when the U.K. left the EU, losing European clients and business and it argues that to keep London competitive with other financial centers like New York or Paris the next government should be lowering taxes on banks rather than increasing them.

It’s not something that Labour looks likely to support and for the Tories there are credibility issues at stake. Both parties want to show voters they won’t be reckless with the economy or give in to pressure from their fringes.

Short-lived Prime Minister Liz Truss, whose massive unfunded tax cuts caused government bond prices to nosedive and pension funds to wobble, left Sunak trying to reestablish an image of stability.

“Especially after Liz Truss’ mini budget, it is an extremely difficult backdrop for the Tories to realistically cut the tax burden in the City,” said McKee.

Bankers still hope a new government could get rid of one hated tax in particular: the bank levy, which raises money to protect people’s deposits if a bank fails.

“While we understand short term it’s going to be tricky, we do want government to review and ultimately phase out the bank levy,” said White.

The tax on banks’ balance sheets, which also dates from the financial crisis, goes to the U.K. government every year — unlike in the EU where it fills a specific rainy-day fund that will be complete by the end of 2024.

But phasing out the levy could be a double-edged sword. The International Monetary Fund said in a July report Britain should “build up a prefunded deposit insurance fund” to give it more financial firepower.

Udaibir Das, a former IMF official who led a previous review, said the problem is without a bespoke fund the money to protect depositors depends on the Treasury’s “fiscal will and space” to provide loans in a crisis.

And creating a separate pot of money could involve more, rather than less, taxes upfront for the banks — something that has so far not tempted any politicians.

But the City of London knows that might not last.

Discussing Italy’s botched windfall tax plan, Lorenzo Codogno, a former Italian treasury ministry official, told POLITICO that “if you shoot the banks you are very popular.”

Banks in Britain know the same applies there.