Speech by Andrea Enria, Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, at the press conference on the 2023 SREP results and the supervisory priorities for 2024-26

Frankfurt am Main, 19 December 2023

Jump to the transcript of the questions and answers

Introduction

Today we are publishing the results of our annual supervisory review and evaluation process, or SREP, for the European banks under the ECB’s direct supervision. The SREP reflects supervisors’ general assessment of the banks’ risk profile and the overall viability and sustainability of their business. This assessment first determines the amount of additional own funds − on top of minimum regulatory requirements – we as supervisors require banks to maintain in order to be resilient to the risks they face. The assessment also determines what actions we ask the banks to take to be better able to effectively manage risks and ensure their business model is prudentially sustainable.

We are also publishing the SSM supervisory priorities for 2024-26, which outline ECB Banking Supervision’s medium-term strategy for the next three years.

In 2023 European banks have proven resilient to the macroeconomic challenges arising from higher inflation and the accompanying rise in interest rates, the low growth of real GDP, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, the resilience we are seeing should not lead to complacency as there are still significant uncertainties and downside risks. Economic growth will continue to be dampened as the ECB’s monetary policy tightening and adverse credit supply conditions feed through to the real economy and as fiscal support is withdrawn.

Moreover, the banking turmoil in March highlights the importance of taking a prudent supervisory approach. Although this episode did not significantly affect our supervised banks, it underscored the risk that rapid interest rate adjustments may cause market instability.

Against this backdrop, the risk assessments performed in this SREP cycle did not result in significant changes in banks’ scores and Pillar 2 requirements. This reflects a recognition of banks’ strength in quantitative metrics for both capital and liquidity. However, this strength needs to be balanced against persistent concerns about the quality of their governance and risk management practices in the face of a deteriorating risk outlook.

The outcome of the SREP is also reflected in our strategic priorities for the years ahead. Our supervisory priorities for 2024-26 are centred on strengthening resilience to immediate macro-financial and geopolitical shocks, accelerating the remediation of shortcomings in governance and climate-related and environmental risk management, and enhancing digital transformation and operational resilience.

Overall resilience of the banking system

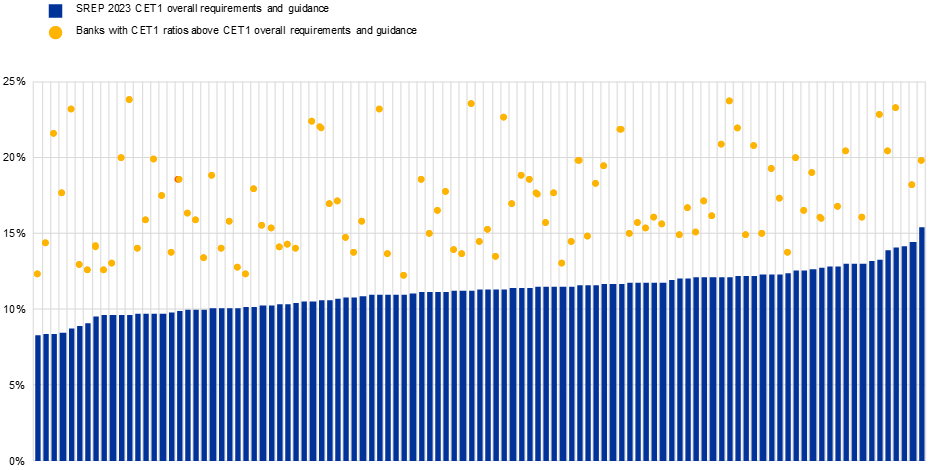

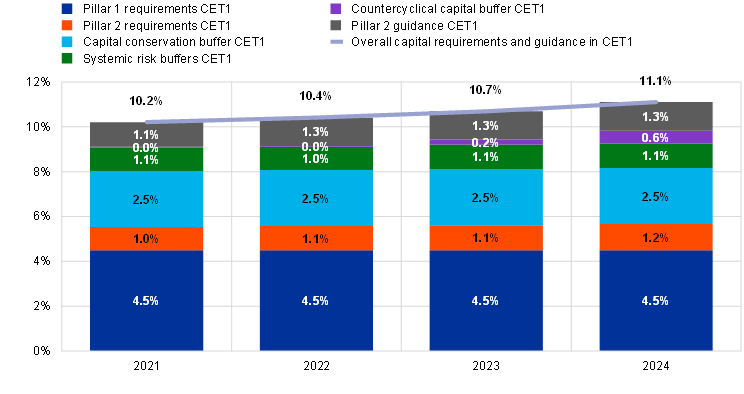

Let me begin by looking at the current prudential status of significant banks. These banks generally have robust capital and liquidity positions. The average Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio stood at 15.7% in the second quarter of 2023, up from 15.0% in the same quarter of the previous year.

All significant banks have reported CET1 ratios that exceed the requirements and guidance applicable in 2024.

This year’s stress test, characterised by the harshest adverse scenario since the inception of European banking supervision, buttresses our view on the resilience of the sector as a whole. Significant banks reported around €70 billion of unrealised losses on securities at book value. This amount is contained compared with that reported by banks in the United States, where valuation losses played a key role in the spring 2023 turmoil involving regional banks. Furthermore, available analysis shows that unrealised losses in the banks we supervise would also remain manageable under adverse scenarios of further interest rate hikes.

Chart 2

Distribution of significant banks’ CET1 ratios relative to new requirements and guidance

(percentages)

Sources: ECB supervisory banking statistics and SREP database.

Notes: Pillar 2 CET1 requirements as per published list of Pillar 2 requirements (P2Rs) as at the first quarter of 2024 and Pillar 2 CET1 guidance as per EBA Stress Test 2023. CET1 ratios are as at the second quarter of 2023 and capped at 25 percent. Systemic buffers (global systemically important institution (G-SII), other systemically important institution (O-SII) and systemic risk buffer (SyRB)) and countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) are the levels anticipated for the first quarter of 2024 and included in the 2023 CET1 requirements and guidance. Each blue line represents a significant bank’s overall capital requirements and guidance in CET1. For some banks, a fraction of CET1 headroom might be used to cover shortfalls in AT1/T2, and therefore the headroom may be lower, but still above overall requirements and guidance.

Asset quality is still strong: the aggregate non-performing loan (NPL) ratio of supervised banks remains near historical lows.

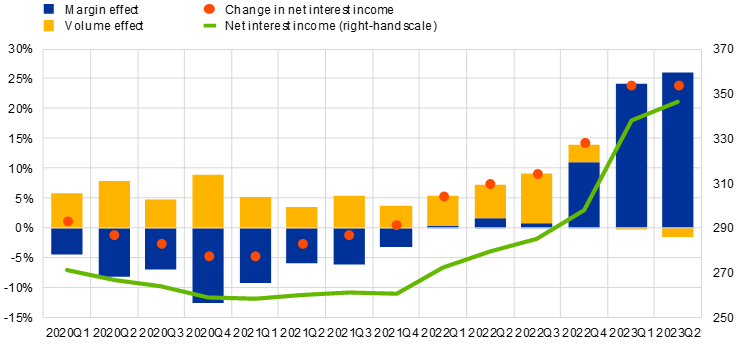

In 2023 banks saw a notable uplift in profitability, driven by the steady and rapid transition from a prolonged period of low interest rates to a consistent fast-paced increase over the past 18 months. In the second quarter of 2023, banks’ average return on equity reached double digits for the first time since the start of the banking union, largely due to wider net interest margins resulting from the rate hikes.

Chart 4

Return on equity annualised composition

(percentages)

Source: Supervisory reporting.

Notes: Chart displays linearly annualised profitability figures. The number of significant institutions per reference period changes in line with updates to the list of significant institutions by ECB Banking Supervision.

Chart 5

Decomposition of growth in net interest income

(left-hand scale: annual percentage changes and percentage point contributions; right-hand scale: EUR billions)

Source: Supervisory reporting.

Notes: Chart displays year-over-year growth rates for linearly annualised net interest income. The number of significant institutions per reference period changes in line with updates to the list of significant institutions by ECB Banking Supervision.

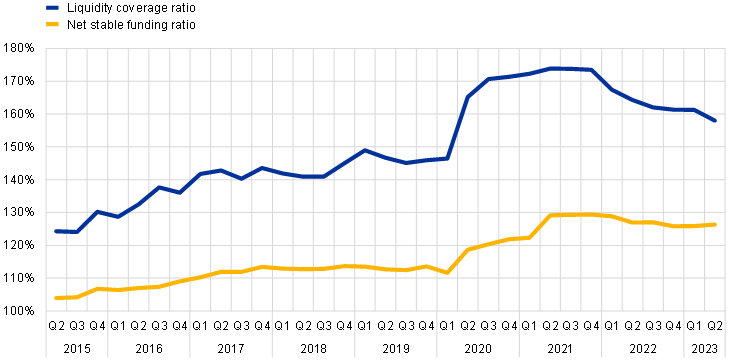

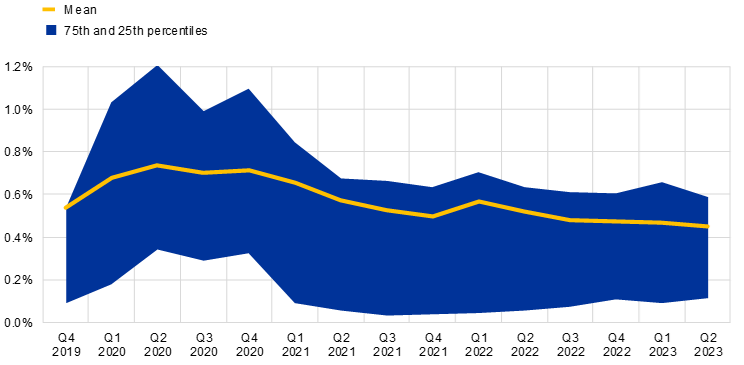

During 2023 banks under our supervision also stayed resilient with regard to their liquidity and funding. Average liquidity coverage ratios remain well above the regulatory minima and declined only slightly, from 164% to 158%, following the shift in the monetary policy stance.

Chart 6

Liquidity and funding ratios

(percentages)

Source: ECB supervisory statistics.

Note: NSFR data prior to the second quarter of 2021 and LCR data prior to the third quarter of 2016 are derived from short-term exercise data.

On average, banks could rely on excess liquidity and a diversified funding base, including their issuance of wholesale funding, to smoothly compensate the ongoing withdrawal of the targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO). Together with robust capital and liquidity buffers and contained amounts of unrealised losses on securities portfolios, a diversified depositor base was a key factor in shielding the sector from the turmoil in the United States and Switzerland during the spring.

These events, formidable in their scope and impact, have tested the robustness of our significant institutions, which have, thus far, withstood these trials with solidity.

Risk outlook

But banks also need to be resilient and vigilant to the evolving risk environment.

And if anything, the events of spring 2023 showed that in times of quick macroeconomic adjustments and heightened uncertainty, market players look beyond regulatory metrics and standard key performance indicators. In particular, they scrutinise banks’ economic value and look for any signs of weakness in their business models.

The economic outlook is marked by considerable risks and uncertainties. Banks will need to grapple with the challenges of tighter financing conditions, persistently elevated inflation, and ongoing geopolitical tensions. The most recent macroeconomic forecasts suggest a notable slowdown in economic activity. Short-term projections of growth in real GDP have been revised downwards for 2023 and 2024.

Downside risks for banks are growing.

Let me first highlight the risks to profitability.

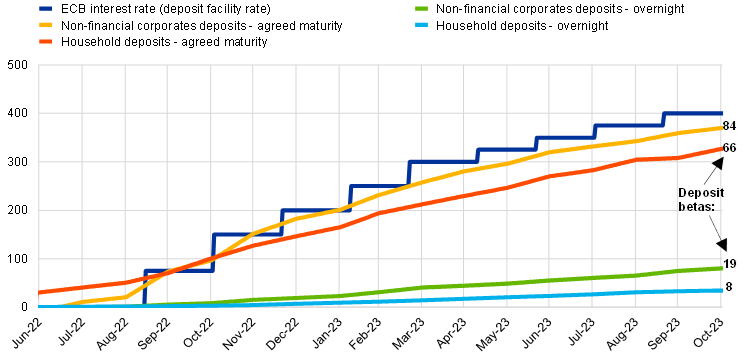

In the current hiking cycle, euro area banks have been slower in passing policy rate increases to depositors than they were in previous cycles. This delay is partly driven by the availability of excess liquidity at banks at the start of the hiking cycle. At the same time, banks placing greater reliance on the ECB’s TLTROs and those that are delaying repayments in that scheme so far do appear to have increased their deposit rates to a greater extent. As these banks complete their TLTRO repayments, they will be likely to intensify the competition for deposits, thereby pushing up the rates offered to depositors.

The normalisation of monetary policy is thus likely to further weigh on banks’ cost of funding and interest margins in the future. Profitability will also be challenged by emerging downside risks, including credit risk and fair value losses.

Chart 7

Evolution of aggregate deposit rates of euro area banks and deposit betas as of October 2023

(ECB interest rate (deposit facility rate) in basis points and deposit betas in percentages)

Chart 8

Euro area banks’ deposit betas in current and historic hiking cycles

(1999-2023, percentages)

Sources: MIR, BSI and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observation is for end-October 2023. Deposit betas refer to the sensitivity of a bank’s deposit rates to changes in ECB monetary policy interest rates (deposit facility rate). For example, if a bank has a deposit beta of 50%, it means that its deposit rates are expected to move halfway between the change in ECB deposit facility rate; if ECB deposit facility rate increases by 100 basis points, then the bank’s deposit rates would increase by 50 basis points.

These concerns − coupled with investors’ disappointment about some governments introducing taxes, levies or other public policies adversely affecting banks’ net profits − are also reflected in the fact that current market valuations of euro area banks have not substantially exceeded pre-pandemic levels. Notwithstanding the progress made in recent years, persistently low price-to-book ratios indicate that investors remain sceptical about the long-run sustainability of banks’ elevated earnings.

Asset quality remains an area of attention.

The quality of bank assets in the euro area may deteriorate due to potential geopolitical risks, or because high inflation and tighter financing conditions are affecting the ability of households and non-financial corporates (NFCs) to service their debts. Although NPL ratios within the banking union remain low, rising borrowing costs and weaker demand could broadly affect credit quality.

In fact, there are emerging indicators that asset quality is already starting to deteriorate. The Stage 2 ratio for household loans, particularly consumer loans, has seen an uptick. Similarly, corporate bankruptcies and default rates have increased, moving up from the record low levels seen during the pandemic.

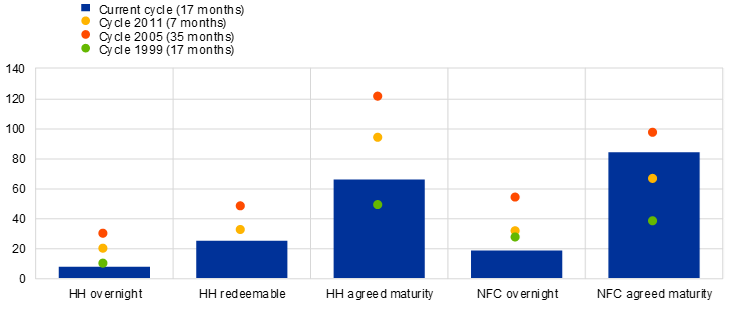

In the real estate sector, residential and commercial real estate markets are experiencing a downturn. Euro area residential real estate prices exhibited a year-on-year decline in the second quarter of 2023. And the outlook for commercial real estate firms has continued to deteriorate amid falling tenant demand and negative credit rating actions. In the current cycle, borrowers in this lending segment are facing increasing refinancing risk, particularly for bullet or balloon loans.

Chart 9

Growth rates of euro area real estate prices

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: ECB and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for the second quarter of 2023 for residential property prices and the commercial property price indicator and for the third quarter of 2023 for rental prices.

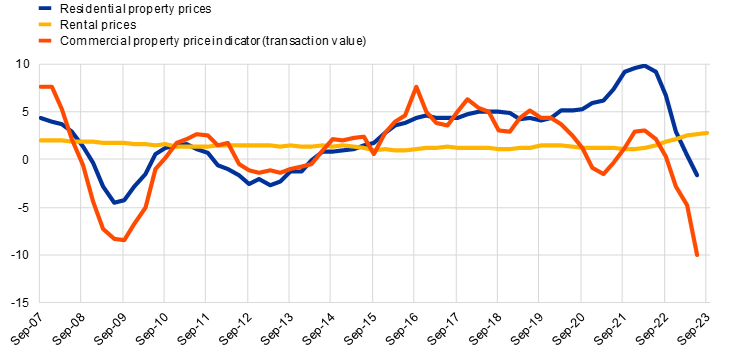

Yet despite the prevailing uncertainty and the emerging risks from an economic downturn, banks have so far not adjusted their cost of risk, which on average stabilised to around 45 basis points.

Chart 10

Cost of risk

(percentages)

Source: ECB supervisory statistics.

Notes: The mean represents an average across significant banks weighted by total loans and advances.

Operational risk, in particular IT/cyber risk, remains elevated, with persisting threats stemming from the geopolitical environment. The number of cyber incidents reported by significant institutions surged in the first half of 2023. Although the impact of such attacks remains contained, they highlight the significant exposure of the banking sector to the evolving cyber threats due to the Russian war in Ukraine, among other factors. Ransomware attacks are especially on the rise, with banks being increasingly affected by evolving extortion techniques.

Additionally, the non-bank financial institutions (NBFI) market has grown significantly, bringing risks associated with common exposures and heightened counterparty risk in a less transparent marketplace.

Chart 11

Significant cyber incidents reported to the ECB

(number of reported incidents)

Source: ECB cyber incident reporting.

Note: Cut-off date: 1 December 2023.

SREP assessment 2023

Let me now turn to the SREP assessment, which was carried out against the backdrop of this deteriorating risk outlook.

As part of this year’s SREP, we focused on persistent, and in some cases long-standing, weaknesses in risk management, governance and internal controls.

As I noted a moment ago, by quantitative measures such as capital ratios and liquidity positions, as well as improved profitability and cost efficiency, banks are robust. Still, weaknesses continued to emerge from qualitative assessments in areas like risk management and governance.

For instance, we identified substantial shortcomings in areas such as risk data aggregation and reporting, management body effectiveness, compliance, and risk management functions. For many institutions, these areas have shown no progress, or have even deteriorated compared with the SREP findings of the previous year. The March turmoil in US and Swiss banks further underlined the importance of strong governance and robust risk controls even when prudential ratios show little cause for concern.

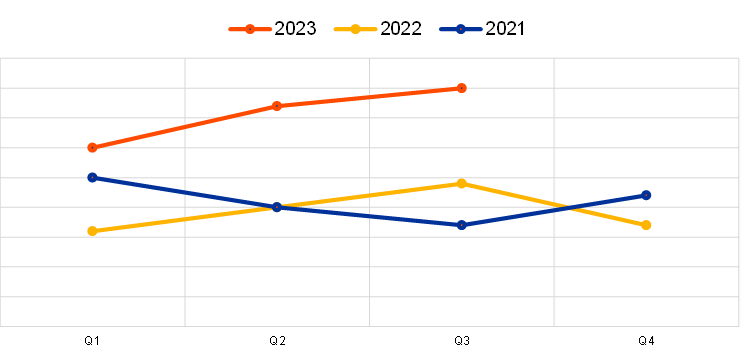

Against this backdrop, our overall SREP assessment is, on aggregate, stable compared with the previous year.

In this regard, the distribution of the overall SREP score for 2023 saw a subtle shift, with a slight increase in the proportion of banks receiving scores of 2 minus, 3, and 3 minus, and a corresponding decrease in the scores of 2 plus, 2, and 4. As a result, the number of banks receiving the lowest SREP score of 4 declined, which reflects improvements in business models and profitability risks as well as capital adequacy. The average overall SREP score did not change.

Pillar 2 requirements (P2Rs) for CET1 capital increased slightly, with an average of 1.2%, compared with 1.1% in 2022, and a median of 1.27% compared with 1.21% last year.

The 2023 SREP cycle resulted in non-performing exposure (NPE) P2R add-ons for 20 significant institutions. In these cases, a shortfall was identified as the cover for risks arising from aged NPEs was assessed to be inadequate. Eight banks received a leveraged finance add-on.

For six banks, a P2R leverage ratio add-on was applied on top of the 3% leverage ratio requirement. Pillar 2 guidance for the risk of excessive leverage was issued for seven banks.

In addition, three idiosyncratic quantitative measures were included for liquidity risk. Two of these measures required a minimum survival period[1] and the third imposed an additional currency-specific liquidity buffer.

Our qualitative measures have primarily targeted areas such as internal governance, credit risk and capital adequacy, with a marked increase in measures related to liquidity risk and interest rate risk in the banking book (IRRBB), triggered by the evolving macro-financial environment.

Chart 12

Overall SREP scores by year

(percentages)

Source: ECB SREP database.

Note: 2021 SREP values based on 108 decisions; 2022 SREP values based on 101 decisions; 2023 SREP values based on 106 decisions. There are no banks with an overall SREP score of 1. Rounding differences might apply throughout the document.

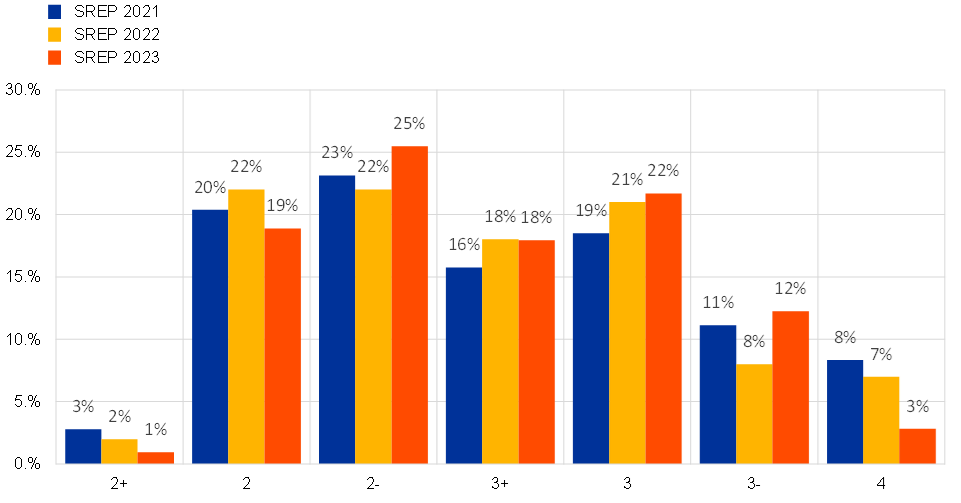

The weighted average of overall capital requirements and guidance to be met with CET1 capital has remained relatively stable over recent years. For 2024, the aggregate capital requirements are estimated to increase slightly to 11.1% of risk-weighted assets (RWA), following 10.7% applicable in 2023.

Chart 13

Evolution of overall capital requirements and P2G in CET1

(percentages of RWA)

Source: ECB supervisory banking statistics and SREP database.

Notes: The sample selection follows the supervisory banking statistics (SBS) methodological note for 2021 (the first quarter of 2021 SBS sample based on 114 entities), 2022 (the first quarter of 2022 SBS sample based on 112 entities) and 2023 (the first quarter of 2023 SBS sample based on 111 entities). For 2024, the sample is based on 107 entities with applicable P2Rs in January 2024. The chart shows RWA-weighted data as at the second quarter of 2023. “Overall capital requirements” means Pillar 1 minimum requirements + Pillar 2 requirements + combined buffer requirement (capital conservation buffer + systemic buffers (G-SII, O-SII, systemic risk buffer) + CCyB). The reference date for the combined buffer requirement is the first quarter of in each year. For the first quarter of 2024 the buffers are estimated based on announced rates applicable at this date. P2G is added on top of overall capital requirements. Under CRD V, P2R capital should have the same composition as Pillar 1, i.e. at least 56.25% should be CET1 and at least 75% Tier 1.

Taking a longer view, over the past decade the ECB has maintained generally steady SREP scores. The overall SREP score across all elements was 2.6 in 2015 – and it is 2.6 today. This stability, however, does not mean that the banks have not improved over the last decade. The SREP offers a relative assessment based on the idiosyncratic risk profile of individual institutions and their ability to rapidly address shortcomings identified in the course of the supervisory process. Our supervisory stance pursued a gradual improvement in banks’ practices across the board and our expectations became more demanding in the light of the daunting challenges raised by the sequence of shocks and the uncertainty of the external operating environment.

In an international context, when we compare our supervisory stance and capital levels with those of major jurisdictions like the United States and the United Kingdom, we find that our banks are well aligned. This balance demonstrates our ability to maintain stringent yet fair supervisory standards, ensuring the safety of banks and stability in the financing of the economy, in good as in bad times.

Supervisory priorities

Let me now turn to our supervisory priorities for 2024-26.

While the risk landscape has evolved since last year, the supervisory priorities and corresponding activities set out in 2022 remain valid overall. They still address the main vulnerabilities in the banking sector, both from a cyclical and structural perspective.

The three overarching priorities for the next three years focus both on the near-term risks to the banking sector and the need to tackle more structural medium-term challenges.

Our first priority targets a more short-term horizon, within which banks need to strengthen their resilience to immediate macro-financial and geopolitical shocks.

Figure 1

Supervisory priorities for 2024-26, addressing banks’ identified vulnerabilities

Source: ECB.

Notes: The figure shows the three supervisory priorities and the corresponding vulnerabilities that banks are expected to address over the coming years. ECB Banking Supervision will carry out targeted activities to assess, monitor and follow up on the identified vulnerabilities. Each vulnerability is associated with its overarching risk category.

Given the higher interest rate environment, we have broadened our focus on liquidity and funding risks and IRRBB. Targeted activities will review banks’ asset and liability management governance and strategies and assess the adequacy of the assumptions underpinning some of their behavioural models. Supervisors will also evaluate banks’ resilience to short-term liquidity shocks and the credibility and soundness of their liquidity contingency plans. We will continue efforts to review how banks are managing IRRBB and how sound and reliable their funding plans are. Credit risk will remain an area of heightened attention, with continued focus on commercial and residential real estate lending and counterparty credit risk exposures to non-bank financial institutions.

To follow up on the weaknesses identified in the SREP assessment, we will be putting more emphasis on banks remediating long-standing findings. If remediation is slow or inadequate, we will respond in a timely and effective manner and escalate where necessary to prompt institutions to speed up their progress.

This objective is captured by our second priority – to request banks to accelerate effective remediation of shortcomings identified in internal governance and complete their alignment with our supervisory expectations on the effective management of climate-related and environmental risks.

This builds on the ECB’s decision to escalate its supervisory intervention on leveraged finance in 2022. To address concerning signs of risk build-up as well as a protracted attitude of complacency on the part of banks, we introduced a targeted capital add-on in banks’ Pillar 2 requirements.

We have taken escalation further this year already, and it concerned climate and environmental risk management. A number of banks did not meet our March 2023 interim deadline to perform an adequate materiality assessment of the impact of climate-related and environmental risks across their portfolios. As a result, we issued binding supervisory decisions requiring banks to remediate shortcomings in their risk controls in this area, including a potential imposition of periodic penalty payments if banks fail to comply.

We continue to be concerned about governance, as some banks have failed to adequately address significant weaknesses in their management bodies’ functioning and steering capabilities, and in risk data aggregation and reporting capabilities, which are essential for banks’ overall assessment and steering of their risk exposures. From 2024 on, the ECB will increasingly apply escalation mechanisms and tools, possibly including enforcement measures and sanctions, to ensure that banks address these shortcomings. Following a public consultation, the Guide on effective risk data aggregation and risk reporting will be published in 2024 to reinforce supervisory expectations. This will be supported by targeted reviews, on-site inspections and engagement with banks showing persistent shortcomings.

As for other structural medium-term challenges, our focus will be on ensuring further progress in digital transformation and setting up robust operational resilience frameworks. The ECB plans a thematic stress test on cyber resilience in 2024 to assess banks’ ability to respond to and recover from cyberattacks. The stress test will confront banks with a severe cyber-related scenario, assessing their operational capacity to manage and recover from it. The outcomes will be integrated into the 2024 SREP assessment.

Transparency and methodology

Finally, we are continuing to enhance transparency of our supervisory activities and today are publishing a number of new methodologies. This complements the existing public disclosure of credit and market risk methodologies on the ECB’s banking supervision website with more information about the risk control framework. These disclosures include new information not only on SREP methodologies in credit risk and market risk but also on governance and business model assessment.

Over and above the outcome of the 2023 SREP cycle, this key annual supervisory process has matured sufficiently to allow reflection on how to make it fit for the challenges ahead. In April 2023, the ECB published the results of an external assessment of the SREP, which includes recommendations for the further evolution of the SREP and improvements of the effectiveness and efficiency of supervision. The report was drafted by a group of independent experts appointed in September 2022.

We started carrying out some of the report’s recommendations in the 2023 SREP cycle already. For example, as part of the thorough implementation of our risk tolerance framework in all supervisory processes, we introduced a new multi-year SREP assessment to allow supervisors to better calibrate the intensity and frequency of their analyses, in line with the individual banks’ vulnerabilities and broader supervisory priorities.

We will take the report’s other recommendations into account in a review of our internal processes in time for the 2025 cycle.[2] In particular, we will review our approach to risk scoring in the SREP and the process for determining Pillar 2 capital requirements.

Thank you very much for your attention. I now look forward to your questions.

I have two issues I’d like to address. The first is to do with the leverage ratio requirement add-ons. First of all, is there any overlap between the requirement add-on and the guidance add-on? Do they relate to the same banks? Could you maybe tell us what caused you to impose these add-ons? Was it banks having excessive derivative positions? Was it securities financing? Was it step-in risk? What’s got you worried and what are you hoping to address with that?

Then on liquidity, the issue involving three banks is very exciting: could you tell us a bit more about that, about how long the survival period is? Is it longer than the four months which you had back in the 2019 test? Is the third bank with the foreign currency problem a G-SIB and is the currency the US dollar? And then on a personal note, we journalists don’t praise the people we report about for good reason. But I would like to say thank you for the added transparency and engagement that we’ve seen over the last five years. It hasn’t gone unnoticed.

Thank you very much for your questions and also for your comments, which I of course appreciate. On the leverage ratio requirement, you are spot on. Basically we are looking at those particular risks that can cause excessive leverage, such as banks which have particularly large derivative positions or securities financing transactions. An additional element is also an excessive variability around reporting days that might signal window-dressing behaviour by the banks. For those banks, we generally use a leverage ratio requirement add-on. For the Pillar 2 guidance, it is basically the same concept that applied in the stress test. We use the same methodology as for the Pillar 2 guidance in general. We look at how the leverage ratio would develop in a stress scenario. And for those banks in the bucket with the highest depletion, of course, that can challenge their continued compliance with the leverage ratio requirements – then we have a leverage ratio add-on.

On the survival period: it is not a very mechanistic definition. We already use the survival period for banks that start experiencing liquidity problems. We basically see how long these banks would survive, based on their own means. We see the flow of payments that the banks should face in the coming days and weeks, and we see how much they have in liquid assets to basically fulfil those payments. We don’t have a threshold, but when this survival period gets a bit low, then we ask the banks to beef up their available liquid assets a little bit. On the currency: I would not comment on a specific currency or bank, also because I don’t have it in my mind to be honest with you.

The first question is about Russia. How happy are you with the progress banks are making on managing their exposures to Russia? Is there any laggard that still doesn’t meet your requirements? The second question is about liquidity and specifically the minimum reserve requirements. Have you done any simulation as to what would happen to banks – and to different types of banks – if your brethren on the other side, not of the building, but of Frankfurt raised the minimum reserve requirements for banks? How would the sector cope and particularly banks with less liquidity?

Since the start of the war we have had a reduction in the region of 47% in overall exposures towards Russia, both cross-border exposures and exposures in subsidiaries in Russia. So there was a significant downsizing of exposure. Of course we have also seen differences in the ways in which banks have reacted. We see that for some banks having establishments in Russia in particular, there has also been an increase in payments especially in non-Russian currencies – in US dollars, euro, yuan and the like. This has meant that we still had to address recommendations to banks to further downsize their businesses and to be particularly attentive to risk control. Of course we have a concern that banks are not always in a position, also due to this particular situation in Russia, to exercise in-depth scrutiny over the internal controls of the subsidiaries in Russia. This source of concern is something which is driving us to exert further pressure on the banks to continue and accelerate these downsizing processes. And of course we have also recently seen some banks exiting from Russia. Although it’s painful because it comes at a cost, this is still possible, so we also invite banks to consider this avenue as far as they can.

On the issue of minimum reserve requirements, as you correctly said this does not fall within the remit of ECB Banking Supervision. We know that there is a review of the operational framework for monetary policy. We are engaging with our colleagues on the central banking side and, as soon as there are options to consider, we will assess the impact on banks. But at the moment I must stress that the President made it pretty clear that the main change was done in June this year in terms of remuneration. And for the moment, this is what’s on the table.

You mentioned the risks involving commercial real estate in your speech and the ECB asked all banks at the beginning of the year what their exposure to Austrian real estate group Signa was. As a consequence, all banks stopped lending money to Signa and it filed for insolvency in November. Henning Koch, the CEO of Commerz Real, said last week that the ECB’s request was one of the main reasons for the breakdown of Signa. So my questions are, do you also think that the ECB was partly responsible for the breakdown of Signa? And more generally, how do you manage the side effects of your supervisory measures – or do you not care about them at all?

Well, thank you for the question. This is a quite bizarre reading of what happened. In general, everybody acknowledges that there is a risk in commercial real estate exposures. The price levels of commercial real estate have gone down 10% already. If you look at the valuations of real estate investment trusts, these are down between 34% and 40%, which means that the market expects further reductions in prices. Banks have significant exposures to commercial real estate. So – surprise surprise – the supervisors go and look into these exposures, not only exposures to certain developers but to all developers. Since 2022 we have done a number of targeted reviews, deep dives, on-site inspections and campaigns. And in all these cases, whenever we found that banks did not have appropriate provisions against these exposures, we actually requested the banks to step up these provisions. By the way, in doing so, we don’t do it all ourselves. We also rely on experienced and trusted advisers specialised in the evaluation of real estate. An additional strength of European banking supervision is that we can compare banks in different countries which have common exposures to the same real estate developer or even assisted by the same collateral, and they can have very different valuations of these exposures. We can challenge the banks which have less conservative, less prudent valuations. That’s our supervisory bread and butter. So generally, when we ask banks to raise provisions it is because we see higher risks. We don’t only do this for commercial estate exposures. We do it as part of our on-site work in all areas, like leveraged financing or consumer finance. In general, the nexus is from higher risk to higher provisions requested by the supervisor. It is not that higher provisions requested by the supervisor generate higher risks. That’s something that I would find bizarre. I don’t see that happening. We are just doing our normal supervisory work.

In this case, you specifically asked for the exposures to a certain company, which many people told us was kind of unique. And the question was, do you in general look at the side effects of such measures?

Let me again explain what supervision is about. When our site inspectors go on site, what they do is called “credit file reviews”. So they open the drawer, they take out the file on the exposure to a counterpart and they see whether this exposure is correctly valued. Now as I said before, they may come to the conclusion that the bank is not properly valuing this exposure, because the collateral is overpriced or maybe because the risk parameters that determine the capital coverage for these exposures, or the provisions that the bank set aside for these exposures, are not appropriate. Our inspectors normally request the banks to adjust these valuations, to provision more, or to revise the risk parameters for these exposures – this is our bread and butter supervisory work. I know that in some countries this was not a common practice, but it has been common practice across most of Europe for a long time. So that’s simply what we are doing if we go there and we see that the bank does not have prudent valuations of its exposures. This we do not only for Signa, or any other commercial real estate developer, but for all the credit files we review in every on-site inspection. And to give you a figure, this year we plan to do 130. So the idea that we are targeting one borrower is simply a flight of fancy. It is not true. Here, there are people disseminating fake news. We should also ask ourselves why such news is in the press, because we always keep such things confidential. You don’t know about the other counterparts we wrote about, because nobody went to the press to say they had been targeted. So there is a little bit of spin on the narrative, that I would advise you to check when you publish your articles.

You’ve made climate and environmental risks one of your priorities and you’ve talked about periodic penalty payments and bank-specific capital add-ons. There was a report yesterday from the ECB suggesting you might also introduce a new risk buffer that would kind of introduce an extra capital add-on for exposures to particular polluting sectors or to geographies that are prone to flood risk. Are you, as a supervisor, planning to introduce these measures that were floated in this report yesterday? Or what else might you do in order to encourage banks to get out of fossil fuel sectors?

Frank Elderson: Thank you very much for this question. First, of course we are a microprudential supervisor, not a macroprudential supervisor. So others might also be active here. But maybe to take a step back and explain a little bit, because you mentioned the periodic penalty payments. The Chair has mentioned those as well. A step back to what our strategy is and what we have been doing over the past years. I am taking you on a little journey. In 2020, we published supervisory expectations on climate and environmental risks and then in 2021 we asked the banks to do a self-assessment. And actually, banks have been very honest in doing that self-assessment, by saying that there was still quite some way to go for them to comply with our expectations. We asked the banks to prepare an action plan and we also asked them how long they think they need to ensure full compliance with our expectations. And 80% of the banks were actually very clear. They said: give us until the end of 2024 and we will get this done. So then in 2022, we did a thematic review where we actually looked at all banks. We looked at them, not just at their self-assessment but also within our own thematic review. And we came to the conclusion that too many banks still had too much work to do. I remember saying at the time that the glass was not even half full. So then we announced that we would expect full compliance with our expectations from all banks by the end of 2024, as well as a number of interim deadlines to make sure that we could follow up in the meantime. The first interim deadline was by March of this year, so March 2023. And a number of banks had just not done their homework sufficiently. And this was important homework, because it has to do with a risk materiality assessment, which is actually the very first step that you need to do if you want to manage your risk in an adequate manner. So for a number of banks, we have indeed issued what we call combined decisions, which stipulate that if, after a further grace period – because of course we are proportional – banks still do not comply with the expectations that they had to meet by March 2023, they would then also incur periodic penalty payments. If that were then indeed to be imposed, that would also be published on our website. We are not there yet, but this is something that might well happen. Looking forward and then maybe wrapping up, we have also set a second interim deadline by the end of this year, at the end of 2023, and then as I said the final deadline by 2024. We look on a bank-by-bank basis, but this is by and large the process that we go through. And it is clear that this is in line with one of our key supervisory priorities, as the Chair has said. And we all know that today, we are not in a 1.5 degree scenario. We are not in a two degree scenario on the basis of UN figures that were published just before COP28 in Dubai. We are actually in a 2.9 degree scenario. So the amount of physical and transition risk out there is even bigger than we might have thought when we started this whole process. Hence the determination to get this done in time.

Andrea Enria: If I may add one point, Frank, if you allow me to just make an announcement . The Supervisory Board has recently approved a report that will be published shortly, which will focus exactly on ways to measure transition risk, which in my view will be particularly important because I see that this debate is always focused on exposure to brown sectors. What is essential is how the banks will also measure the ability of sectors which are brown to transition. So we will try to develop, to steer a debate on how banks and financial insitutions more generally can measure the transition. Because that will be the key element to manage the risk properly going forward.

In the report today, you see higher risks tied to higher interest rates. But if in 2024 the path is leading to gently cutting rates, if decided here, let’s say in the middle of next year, maybe sooner, while inflation returns back to target of course. In this environment, do you think the risk you outline and the link to the high interest rates will then, if not disappear, then diminish to a large extent?

Well, we already know the risks for banks of a low or even negative interest rate environment. This has played a role for a relatively long period of time in terms of compressing interest margins. Of course, to some extent, also in the past, this was compensated by higher volumes of lending. Anyway, at the moment, for us the point is that there was a rapid shift to a higher interest rate environment. And you know that in general, the asset quality problems materialise with some lag, there is always at least six months, maybe longer, in terms of lag before the tension that is generated by a change in interest rate environment materialises as difficulties for borrowers to pay back their loans. So for the time being, I think that the key issue is still the fact that the current change in the interest rate environment has not yet translated into asset quality problems. We start seeing, as I mentioned, some sectors – we’ve seen consumer finance first, now we have also seen commercial real estate – in which non-performing loans start increasing. Residential real estate is still relatively resilient because, notwithstanding the increase in interest rates, another key determinant – the unemployment rate – has remained pretty positive, there hasn’t been an increase in unemployment and this has been buttressing the strength of residential real estate borrowers. So, again, a sort of landscape that will need to be continuously monitored, and banks will need to continue looking into how this will affect their balance sheet.

Next year, we’ll do a specifically targeted review, as I mentioned, on asset and liability management, exactly because with this variability in interest rates it is important that banks at the same time look at the interest rate risk in the banking book and the impact this could have on their funding and liquidity profile, which is something we have seen at play in particular in the regional banks in the United States. So if there are further moves, whatever the direction, this will be something banks will need to look at pretty carefully.

I was wondering if profitability, also in a context of lower interest rates, could re-emerge as a structural problem of the sector that was just hidden in the last year due to higher interest rates. So do you see risks on that front?

And secondly, what do you consider the main achievements of your mandate, and did you give any advice or recommendation to the next ECB Supervision Chair?

What you mentioned is indeed a concern that we hear from many investors at the moment – as I also mentioned in my introductory remarks. When we ask investors why the cost of equity remains so high and why the price-to-book value of European banks remains so depressed – to be honest, it has improved, it moved from around 50% at the peak of the pandemic to 70% right now, but is still depressed, still below 100% – the answer generally is that the banks have not yet proven that the increase in profitability is here to stay, that it is sustainable.

So there is this concern that this effect will disappear as soon as the pass-through to the deposits is completed, and even more if there are future downward changes to the interest rates. So my view is that this disregards the significant adjustments that banks have made in recent years. Maybe it is an area in which it would be more appropriate to differentiate across banks, so I would expect that there will be more differentiation across banks. There are banks which have been very effective in improving their cost efficiency, for instance, in embracing digitalisation strategies and using them as a new tool to strengthen their business model. Banks which have also refocused their business model maybe via transactions, selling lines of business that were not sufficiently profitable, and maybe acquiring scale in other lines of business that were areas of strength. To me, this type of recovering profitability is here to stay. I think that markets are clearly sceptical, and banks would have to prove that, even maybe in the presence of future declines in interest rates, they will be able to sustain the newly found profitability levels that they have right now. If there is a divergence in performance, of course, that could also be opening some room for consolidation as a way to address these issues.

On the main achievements, I think that the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) is a relatively cumbersome machine. We are here at the ECB, then we have 21 national authorities. We have our own rather complex and burdensome procedures sometimes. I think our main achievement throughout all these series of shocks – starting with the pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and the return of inflation with the rapid change in the interest rate environment – has been our agility, our ability to be very fast in analysing the risk to the banking sector, providing clear indications to the banks, to the markets, communicating swiftly with the markets, providing, when needed, relief measures for banks, or asking for additional prudence in risk management. I think that this has been very effective and I’m very proud of this achievement.

I don’t need to give any advice to Claudia Buch; she’s very experienced, and I have a lot of respect for her. So I’m sure that she will chart the course and continue the development of European banking supervision in a very effective way.

Just a quick question, I’m trying to clarify the various numbers that were given out around the survival period and also the Pillar 2 demands and the Pillar 3 guidance. So, is it that there are eight banks that were given Pillar 2 demands because of leveraged finance, six that were given Pillar 2 because of leveraged finance, and then an additional six that were given Pillar 3 guidance, or can you clarify those numbers for me?

On the liquidity front, we have been doing what I already mentioned. After the turmoil in the spring, there were a lot of question marks about whether we should now overhaul liquidity regulation, significantly review the liquidity coverage ratio, maybe throwing in the bin other regulatory requirements, and restart from scratch.

I’ve always argued that there will never be a regulatory requirement which will cover all the possible contingencies, and that it would be wrong, actually, to calibrate liquidity requirements, liquidity regulations to cater for very extreme business models like Silicon Valley Bank, for instance.

So, for me, we need to maintain the regulatory requirements more or less in that ballpark. There might be some adjustments here and there – Michael Barr mentioned something in the conference that we had a few days ago, and the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision is working on that – but, in my view, no major changes.

Still, we can and should identify banks which are particularly fragile to certain specific metrics, and in those cases intervene with supervisory measures. And this is what we have done.

I mean the survival period, as I mentioned before, is how long a bank can stand on its own feet without relying on extraordinary support from the central bank or other forms of facilities to fulfil its payment schedule as it comes due. And if we see that some banks are particularly short on that metric, then we will ask those banks to buttress their liquidity position.

We had, as I said, two banks on which a specific requirement was imposed in terms of widening the survival period. And one was a specific lack of liquidity in a specific currency.

In terms of leveraged finance, very much in line with what Frank also said for the climate and environmental risks, we specified in a Dear CEO letter and then in a specific guidance what we expect banks to have in place. Banks have been misaligned with our guidance for a long while, and the Supervisory Board clarified that we want banks to fall back into line with our supervisory expectations.

We identified the banks that were farther from our expectations, we asked for remediation, and when this didn’t happen, we started last year to gear up capital requirements.

We had three banks that were targeted with add-ons on leveraged finance last year. One bank exited the leverage finance add-on because the problem was fixed. By the way, the problems particularly targeted the risk appetite framework. The other two stayed in the set, and this year we had an additional six banks for which the add-on was charged because, again, they were not sufficiently fast in falling into line with our expectations.

So we see that there is an effect of these add-ons, and we expect the banks to remedy the shortcomings we have identified as a matter of urgency.

I was wondering, in light of the risk of the deteriorating profitability of the banks in the near future you just addressed, does the ECB have concerns that the bank levies in some countries are affecting the strength of the European banking sector?

As you know, the ECB issued some opinions on interventions made by governments in several countries – in Spain, Italy, Lithuania and Slovenia – identifying some concerns with these types of intervention, highlighting in particular the need to also measure and assess the potential adverse impact that these interventions might have on bank lending and resilience in the longer term.

Personally, I think that the main point is that, as I mentioned before, banks maintain very low valuations. So it is a moment in which governments, and public opinion to some extent, have this impression that banks are excessively profitable, that they have windfall profits, that they are making too much money, while the markets think that they are not profitable enough, so their return on equity remains steadily below their cost of equity. And these interventions, to some extent, reinforce the impression among investors that whenever banks make some profits there will be somebody coming and taking them away from shareholders. So there is a little bit of concern that I have.

Another concern that I have with these measures is that they often target the interest margin, so they don’t consider the provisions. As I mentioned before, this increase in profitability is potentially also linked to an increase in risk, because the higher interest rates are indeed widening the interest margins, but might also increase the credit risk of banks. So we would expect banks to increase provisions, and this would not be reflected in the actual calibration of these measures by governments.

So there are some concerns that we have identified and made public. Ultimately, of course, we are the technical authority, and the final decision on taxes rests with governments and parliaments. We are just trying to give our input to increase awareness of how these measures might impact the perception of banks in the markets and their actual behaviour in terms of lending and provisioning.

My question is on funding, if you can make a comment, because banks had to go through a period of very rapid increase in interest rates. And at the same time they had to repay the targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs), so they don’t have this instrument anymore. How does the European banking system cope with not having this instrument? And do you think that it is useful to have this kind of instrument anyway for banks?

Also, still on finding an instrument, what would you say about securitisation? I heard some banks saying that it is badly needed, but it’s not there. So European banks have one instrument less compared to other banks, especially US banks. But how big is this problem? How important would it be to have securitisation for banks?

So far, the reaction of banks to the shift in the funding environment has been very positive and very robust. Banks have been able to meet the deadlines for repayment of TLTROs. Many banks have anticipated significantly the repayment of TLTROs. And the impact on their liquidity ratios, for instance, was honestly, from our point of view, a little bit of an area of concern. There were estimates that indicated a potential decline in the liquidity metrics, in the liquidity coverage ratios and liquidity buffers in particular, but these have not materialised. As I mentioned in my introductory remarks, the liquidity coverage ratio decreased only slightly from 162% to 158%, notwithstanding a massive repayment of TLTROs. So banks have been able to substitute these extraordinary funding sources with a reduction of reserves or with access to wholesale funding markets, without a major impact on their profit and loss.

So far banks have done pretty well in terms of tackling this funding risk. As I mentioned before, of course, this does not mean that they should disregard the challenges ahead.

There are further chunks of the TLTROs to be repaid. The interest rate environment remains, of course, much more challenging than it used to be. The pass-through will probably increase, and we can already see differentiation across banks. The banks which were weaker, to some extent, in terms of funding capacity and relied more on the TLTROs – those which have postponed, for instance, the repayment of TLTROs – are those which have started offering higher deposit rates to attract new deposit funding.

And when we see the funding plans of the banks, in many cases all of them say that they plan to increase their market share of deposits. Now, of course, not all the banks can increase their market share, so there will be increased competition, and this means that the funding cost will also increase.

In a nutshell, so far so good, but there will be more challenging times ahead.

I saw TLTROs as useful in the specific contingencies in which they were issued, but they should now be phased out, and markets have been well prepared for that.

Securitisation is an important issue. It is true that the securitisation market has not been particularly good in the European Union recently; there was a significant drop with the great financial crisis. Notwithstanding a lot of effort from regulatory authorities to re-establish it on sounder foundations, with simple, standard and transparent securitisations, there hasn’t been an increase in volumes.

There has been an uptick more recently. It might also be that the depressed state of the securitisation market was due to the fact that it was used only to reduce capital requirements. The funding reason was not there because banks were flush with liquidity. Now that the funding market is becoming more challenging, I expect the securitisation market can also recover somewhat.

Of course, we remain distant from the United States. The United States also has Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac which help banks, disposing of their mortgage portfolios on very advantageous terms. But I think, also from a policy perspective, that we need to continue finding avenues to strengthen the recovery of the securitisation market. The European Banking Authority (EBA) has done important work recently. We are collaborating with them and with the Commission, and we expect there to be further initiatives that should support recovery in the market.