This episode originally aired on April 07, 2023

The Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act was signed into federal law in late 1990. It made exhuming Native American remains without tribal consent illegal, and established a framework that would allow tribes to find out which museums and government agencies had remains or funerary objects and seek their repatriation.

Prior to that, Native American gravesites only had protection as archeological sites, said Suzan Shown Harjo, who is President of the Morning Star Institute and is Cheyenne and Hodulgee Muscogee.

“You couldn’t drive down a highway or a back road in the United States without seeing some billboard or sign that said, ‘See the Indian Mummy, two miles over here,’ or ‘An Indian Graveyard Exposed,’ things that would have caused an uprising had anyone desecrated the graves of the townspeople there, the white people.”

It was not just roadside attractions though, according to Dr. James Riding In, a member of the Pawnee Nation, longtime repatriation activist, and retired professor at Arizona State University. He recalls similar displays were in revered institutions as well.

“In 1970, I visited the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Walking through the door there, there was a shelf of human remains, crania. They were all Indian and identified by their Indian nation. We were just a curiosity. We didn’t have human rights, we didn’t have burial rights”

Shown Harjo, who was involved in the writing of NAGPRA and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2014 for her work on native rights, said Native remains were treated as possessions.

“You had people in museums, federal agencies, and private collectors who looked at us as butterfly collections. There are still some of those who think they own us when we’re dead, and that really lead us to repatriation law.”

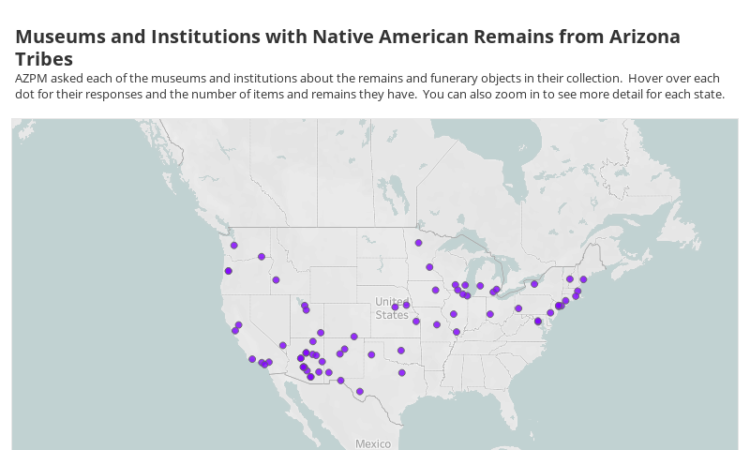

When NAGPRA was enacted, federal officials estimated that the entire project would be completed by 1995. Now, 28 years later, the database assembled by NAGPRA shows 5,626 MNI or minimum number of individuals, and 15,738 AFO or associated funerary objects that can be traced to tribes in Arizona remain in the hands of a museum or government agency.

So, why do so many items remain unreturned almost 30 years after the problem was estimated to be solved?

One reason is there is little information about where some remains came from or which tribe they belong to. For example, at the Sharlot Hall Museum in Prescott, the database says it has one individual and one associated funerary object.

“I mean sometimes you do encounter those objects where you’re like, ‘How did this happen? Why is this here? Who made the decision to say, yes we will take this thing?'” said Jackson Medel, Sharlot Hall’s Curator of Collections and Exhibits. “Now that applies to both what we’re talking about with NAGPRA materials as well as just regular things in the collection that may not seem controversial or strange but do fall out of line with what the institution is intended to do.”

The museum’s collections manager, Alannah DeBusk, can quote the date the museum was founded off the top of her head, June 11, 1928. And the fact that the relatively-small museum is approaching its centennial is part of the problem it has in finding where these remains came from.

“Unfortunately, sometimes you don’t know a lot just based on the information that was collected when those individuals were collected and that is what we are dealing with here.”

Thanks to the museum’s age, many items it owns date to a time when its staff were not museum professionals, and collection and documentation practices were lacking at best.

“When museums started, it was just collect as much as you can, basically. They just collected what they could. Why? I don’t know.”

The museum says it has invited local tribes to examine the remains but has had no luck in identifying which tribe they are connected to.

Medel said that a lack of knowledge about the remains is a problem that is not likely to be solved, no matter how much time, effort or money the museum spends.

“No amount of money is going to give us the name of the people who brought these things to the institution. No amount of money is going to help us identify who these individuals were and where they came from without having some of that information.”

A lack of knowledge can complicate repatriation for museums, but it is also a complicating factor for those trying to find the exhumed bodies of their ancestors.

“Congress did not put any higher standard of identification in the law,” said NAGPRA Program Manager Melanie O’Brien. “It is a simple process by which information that is available should be used to identify the present-day people that are connected to past people.”

NAGPRA states that museums and agencies need only make a good-faith effort in identifying remains using the information they have.

Those efforts, regardless of their quality, are now decades old, and the people who made them may have moved on.

“A lot of times these collections, especially of Native American ancestors, tended to be special projects–special collections–that only a small group of people maybe knew about,” said O’Brien. “And once those people retired or left the institution, there may not be information.”

AZPM talked with one museum curator who had such a problem. He was hired by a Texas museum a few months earlier.

He was surprised by our email, and couldn’t find information beyond what we found in the NAGPRA database despite it having been gathered at some point.

Information that goes beyond statistics is kept by NAGPRA but is only made available upon request by museums and tribes.

That curator said he wasn’t even aware that he could ask for that information.

While time has changed how many institutions deal with Native American remains and funerary objects, that is not the only cultural difference that Native people see.

“There are museums out there that are very influential that are about native people but they’re not controlled by native people,” said Manuelito Wheeler, director of the Navajo Nation Museum. “And for better or worse, that’s how it is.”

Wheeler is Navajo, and has worked at a variety of museums in the past. He said the first-hand cultural experience could help many museums, but beyond that, how large institutions treat remains and repatriation is important.

“They are in the driver’s seat for people’s opinions that are being formed about us as Native people.”

He and Riding In both said many museums are doing well when it comes to their modern practices around Native cultures.

But, he did admit to having an advantage. As a museum that is owned by a tribe, he has an easy fix when he is occasionally contacted by private parties seeking to donate remains or funerary objects.

“If any items that come by the museum here and there, I feel are NAGPRA-related, and there are many items like that, I will ask them to contact the Navajo Nation Heritage and Historic Preservation Department.”

While other museums do not have that close of a connection to a tribe’s NAGPRA office, many that AZPM spoke with said they too have routine interactions with tribal offices.

“Arizona has 22 federally-recognized tribes, and I’d like to think that the [Arizona State Museum] has good relations with all of them,” said Dr. James Watson, Associate Director of the Arizona State Museum.

Watson said the museum has focused its efforts on repatriations to nearby tribes to start and is working its way to the state’s northeast.

But hurdles remain for the Arizona State Museum and others, ranging from expenses to the massive backlog of remains. For some institutions and tribes, those number in the thousands.

For the Arizona State Museum, that number is nearly 4,000 sets of remains still in its care. Watson said that number has halved since he joined the museum.

“We actually have more individuals than [that]. We also have collections from federal agencies that we are managing their repatriation, but the way that we can do that is the federal agency funds us to process their collections,” said Watson.

Watson said that money also helps cover expenses for the Arizona State Museum. It has two employees who work part-time on repatriation.

NAGPRA Program Manager O’Brien said Congress also allocates millions of dollars each year to fund repatriation.

The Department of the Interior is currently in the process of revising its rules around repatriation in the hopes of finishing the job nearly three decades after it started.

“The process for regulations and regulatory change requires a period of public comment, which concluded at the end of January. We’re right now reviewing those comments and working on responses to them. Once the rule is final–if that time frame continues–then yes, we would hope that, for the Native American human remains, this process would have an end date.”

The end date as currently proposed would be two-and-a-half years from when it goes into place.

Another improvement that Riding In said they would like to see is a change to the classification system in NAGPRA, making ‘unidentifiable’ to ‘unidentified.’

“These institutions devised arguments to classify as many of those remains as culturally unidentifiable as possible so they didn’t have to repatriate them. NAGPRA essentially just set up a can to be kicked down the road.”

Harjo notes one prominent instance where a noted paleoanthropologist continues to hold native remains against tribal wishes.

“Professor Tim White at the University of California at Berkeley has the largest collection, which he considers his personal collection, of Ohlone People.”

Dr. White said he does not hold any remains personally.

“I am a Faculty Curator of Biological Anthropology at the U of California, which is responsible for all Federal, State, and UC Systemwide NAGPRA compliance,” he said in an email. “Personalizing grievances is not an effective means of combatting systemic racism.”

The NAGPRA database shows University of California at Berkeley holds the remains of at least 8,279 Native ancestors, at least 5,096 are from California tribes. It also holds 122 remains from tribes in Arizona at minimum.

Even if the pending changes to NAGPRA solve the long-running problem, there is still another issue.

Wheeler, Riding In, and Harjo all noted that there is still the matter of private collections.

Another listing in the database from Arizona is an example of that issue.

One of the remains in possession of the Missouri Department of Natural Resources got there after decades in private hands.

The state ended up with the item in 2009 after it was discovered by the Woodson Terrace Police Department.

A WTPD spokesperson said an officer saw the remains after he was invited into a person’s home while investigating an unrelated robbery.

The person handed the remains over and told the investigator that he had legally bought them at the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show in the 1980s.

No charges were filed.

“There are plenty of places out there that still have sacred objects, that have burial objects, and they got them ‘legally,’ which I mean I think any burial item that you possess is illegal period.”

Shown Harjo said the struggle continues, though she sees a path forward.

“Structural racism includes individuals who just need to be educated and it includes people who are monsters, and everyone in between. What many of us try to do is educate the educatable and get some sort of accountability measures for those who hide behind lack of education or misunderstanding.”

More from The Buzz