After a nearly two-year honeymoon since the inauguration of U.S. President Joe Biden, major rifts are opening up between Washington and its European allies over economic policy. Unless these rifts are handled deftly, the Biden administration’s vision of a new global economic order in which the United States works with allies and partners in Europe and Asia to contain Chinese and Russian ambitions could degenerate into a world of competing economic blocs.

After quietly rumbling for months, the spats burst into the open last week. Thierry Breton, the European Union’s internal market commissioner, announced he would pull out of this week’s meetings in Maryland of the U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council, a key coordinating body for trans-Atlantic economic policy. He said the agenda “no longer gives sufficient space to issues of concern to many European industry ministers and businesses,” pointing to EU complaints over new U.S. subsidies for electric vehicles and clean energy that disadvantage European carmakers and other companies. Instead, he said, he would focus on “the urgent need to preserve the competitiveness of Europe’s industrial base.”

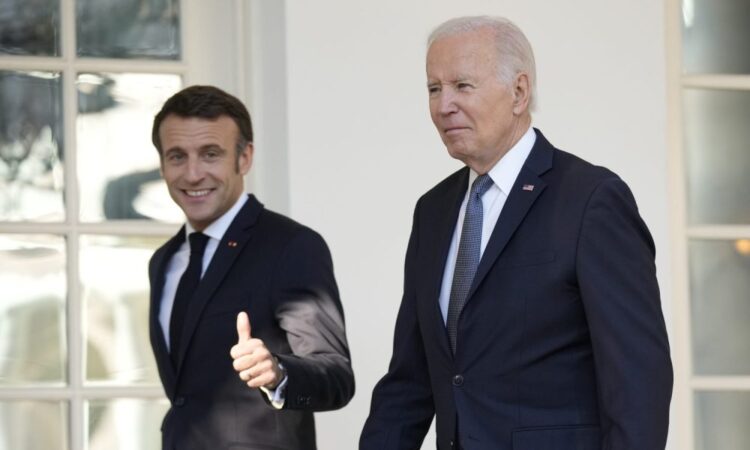

French President Emmanuel Macron, who was in Washington last week to attend the first White House state dinner held since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, said that U.S. subsidies “are very good for the U.S. economy, but they weren’t properly coordinated with European economies.” In advance of the visit, Bruno Le Maire, French minister of the economy and finance, accused the United States of pursuing Chinese-style industrial policy.

After a nearly two-year honeymoon since the inauguration of U.S. President Joe Biden, major rifts are opening up between Washington and its European allies over economic policy. Unless these rifts are handled deftly, the Biden administration’s vision of a new global economic order in which the United States works with allies and partners in Europe and Asia to contain Chinese and Russian ambitions could degenerate into a world of competing economic blocs.

After quietly rumbling for months, the spats burst into the open last week. Thierry Breton, the European Union’s internal market commissioner, announced he would pull out of this week’s meetings in Maryland of the U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council, a key coordinating body for trans-Atlantic economic policy. He said the agenda “no longer gives sufficient space to issues of concern to many European industry ministers and businesses,” pointing to EU complaints over new U.S. subsidies for electric vehicles and clean energy that disadvantage European carmakers and other companies. Instead, he said, he would focus on “the urgent need to preserve the competitiveness of Europe’s industrial base.”

French President Emmanuel Macron, who was in Washington last week to attend the first White House state dinner held since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, said that U.S. subsidies “are very good for the U.S. economy, but they weren’t properly coordinated with European economies.” In advance of the visit, Bruno Le Maire, French minister of the economy and finance, accused the United States of pursuing Chinese-style industrial policy.

The subsidies at issue are part of two massive bills passed by the U.S. Congress earlier this year: the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the CHIPS and Science Act. The former offers as much as $370 billion in subsidies for faster adoption of clean energy in the United States. It includes tax credits for U.S. buyers of electric vehicles—but only if the vehicles are assembled in North America and their components are made in the United States or other select “free-trade partners,” language that would hurt European car companies such as Volkswagen and BMW. The latter bill offers $52 billion in support for semiconductor companies to build new high-end fabrication plants in the United States. European leaders see both measures as unfairly subsidizing U.S. companies, aggravating the continent’s competitiveness challenges, and potentially forcing Europe into a costly subsidy arms race with the U.S. and China.

The Dutch government also pushed back publicly last week against U.S. pressure on its major producers of equipment for making chips, ASML and ASM International, to cut ties with China. The United States has launched a sweeping campaign to block sales of high-end semiconductors and chip-making equipment to China but has yet to persuade allies like Japan and the Netherlands to go along. Dutch Economics Minister Micky Adriaansens told the Financial Times that her country is “very positive” about relations with China and that Europe and the Netherlands “should have their own strategy” on controlling exports to China.

The growing divisions are partly a consequence of Russia’s war on Ukraine. While the United States and Europe have maintained a united front on sanctions against Russia and military aid for Ukraine, Europe has paid a much higher economic price for the conflict. Natural gas prices in most European countries have soared to as much as 10 times U.S. levels, putting European industry at a huge competitive disadvantage. While the United States has helped Europe fill the loss of Russian gas with liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports, it is being sold at the currently inflated market prices. France’s ambassador in Washington, Phillipe Étienne, told Foreign Policy: “We are grateful that the United States provides Europe with LNG, but there are issues about the price.”

Longer term, the disputes center on the conflicting goals of the Biden administration’s industrial policies. On the one hand, the United States wants to build a robust supply chain that reduces China’s role in supplying critical technologies and inputs for the industries of the future. That requires close cooperation with allies—what the administration has termed “friendshoring”—to prevent wasteful duplication and ensure greater resilience of supply. On the other hand, the administration is eager to see the revival of U.S.-based manufacturing, believing the loss of manufacturing—due in part to Chinese competition—weakened U.S. security and harmed the economy. Lost manufacturing jobs also eroded voter support for the Democrats in industrial swing states such as Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Each of the new U.S. measures puts a thumb on the scale in favor of companies investing in the United States rather than Europe or other close partners.

Biden’s Commerce secretary, Gina Raimondo, whose father lost his job of 28 years at the Bulova watch factory in Rhode Island when the company moved production to China, put it clearly in a speech at MIT last week: “Going forward, we are not only going to invent the technologies of the future in America, but we are going to manufacture them here, too.” Not surprisingly, this does not sit well with U.S. allies and other trading partners, who face the prospect of losing markets in China as the United States insists they embrace new restrictions, only to see multinational companies relocate to or expand production in the United States in order to take advantage of cheaper energy and generous subsidies.

The Europeans are not alone in their concerns. World Trade Organization Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala is trying to protect the nondiscrimination norm—the requirement that trade partners are treated equally—that has been at the heart of trade multilateralism for 75 years. She argues that few countries embrace the binary choices being offered by the Biden administration. “Many countries don’t want to have to choose between two blocs,” she said in a speech at the Lowy Institute in Australia. Forcing such choices could damage progress on issues where the United States, China, and other countries have no choice but to work together. She warned that “policy-induced decoupling designed to build resilience and security could end up feeling like an own goal,” harming cooperation on collective challenges such as climate change, pandemics, or sovereign debt distress.

Biden’s words prior to the state dinner with Macron suggest he is acutely aware of European concerns and willing to try to ameliorate them. He said the two leaders “agreed to discuss practical steps to coordinate and align our approaches” and ensure that manufacturing and innovation are strengthened “on both sides of the Atlantic.” Macron echoed that the two sides had agreed to “resynchronize our approaches.” “We can work out some of the differences that exist,” Biden said. “I’m confident.”

The details will not be easy to resolve, though. Biden candidly admitted there were “glitches” in the legislation that should be fixed. But it is unclear, for example, whether the IRA’s language on extending subsidies to goods produced by free-trade partners can be stretched to include the EU. And there are many in the Congress and the administration, as well as in industries such as steel and solar, who are committed to the legislation’s “America first” principle, believing the United States is long overdue for a manufacturing revival. They will push back against an overly generous interpretation of the law.

Biden and European leaders are well aware that they cannot permit a fundamental trans-Atlantic rift to open. More than at any time since the height of the Cold War, the dual threat of Russia and China is forcing the United States and Europe to cooperate and work through economic disputes that might have festered for many years in less stressful times—such as the long tussle over subsidies to Airbus and Boeing.

The high stakes suggest the two sides will find a way through. As Macron put it: “The circumstances mean that we have no alternative but to work together.”