Lucía Pineda Ubau had been working around the clock, sleeping in her newsroom in Nicaragua and covering President Daniel Ortega’s violent crackdown on anti-government protests, when the police stormed in.

They cut the TV station’s news signal, bound her wrists and hauled her away.

In a dark, fetid cell in Managua’s notorious prison known as El Chipote, where the country’s former dictator once tortured the Sandinista rebels, she waited for her next interrogation.

“I clung to God, to prayer,” Pineda, 49, recently told USA TODAY. She was unsure of when she might be freed.

Her arrest had come more than a decade after Ortega, a former Sandinista rebel who led Nicaragua during its fight with U.S.-backed Contras in the 1980s, returned to the presidency and grew increasingly autocratic.

After massive demonstrations erupted in 2018, police and paramilitaries crushed both the protesters and the independent journalists who told the story, driving some like Pineda to prison, and forcing more than 180 journalists into exile.

Among them were Carlos Chamorro, a prominent editor whose offices raided twice before he fled; Néstor Arce Aburto, who livestreamed protests before making a narrow escape; and Octavio Enríquez, whose family faced threats as he reported on corruption.

Today, all of them cover their home country from outside Nicaragua, often from across the border in Costa Rica. Since then, they’ve watched media repression increase in several Central American nations, which experts say reflects the region’s continuing slide toward authoritarianism.

In Guatemala last month, the founder of the newspaper El Periodico, José Rubén Zamora, was sentenced to six years in prison in a money laundering case that press advocates say was retaliation for reporting on corruption. His imprisonment followed the newspaper’s closure the month before. An election next month pits an establishment candidate against an insurgent who has vowed sweeping anti-corruption reforms.

More:What’s happening in Guatemala? How a small country’s elections could have a big impact on the US

In El Salvador, digital investigative outlet El Faro announced in April it was moving its administrative offices to Costa Rica amid what its founder said was a relentless campaign of government surveillance and legal harassment.

Honduras has been one of Latin Americas’ deadliest countries for journalists, Reporters Without Borders said in 2022, adding that opposition media have faced threats and intimidation, forcing some to flee.

The Network of Central American Journalists, formed last year to fight for press freedom, has said they are facing “the greatest obstacles to the free exercise of the profession in three decades.”

The slide of press freedoms in Central America echo a growing global concern as autocratic leaders increasingly label the press an “enemy” and embrace repressive laws such as adopted in 2022 in Russia – a version of which exist in countries such as Nicaragua and Egypt – that criminalize publishing what is deemed as “fake news.”

That’s led an increasing number of journalists to flee countries such as Iran and Afghanistan, the Committee to Protect Journalists reported last month.

In Central America, media repression is the most acute in Nicaragua, the hemisphere’s second-poorest nation. Since 2018, Ortega has forced the closure of more than 50 media outlets by canceling licenses, seizing assets and charging reporters with crimes as part of a wider move to silence dissent and political opposition.

In addition, journalists say, pro-government misinformation troll farms that flood social media and state-controlled news outlets leave some unsure what information to trust.

While the environment for journalism in the United States remains “satisfactory” despite recent slides in its ranking, according to Reporters Without Borders, Nicaraguan journalists working in exile say their stories offer a cautionary tale.

While media repression is often a harbinger of crumbling democracy, it can also be a last line of defense against autocracy, they say, even from abroad.

“In Nicaragua, there is not a single independent media outlet that operates within the country,” Arce said. “Freedom of expression and the press is in a stage of serious deterioration in Central America.”

Despite all the challenges, many journalists working in exile are finding ways to inform residents back home.

For Pineda – who was accused of inciting violence and promoting terrorism — that meant first surviving prison.

Protests and an authoritarian crackdown

By December 2018, Pineda, the news director of 100% Noticias, was eating and sleeping at a Managua TV station that was under virtual siege.

About 150 feet from the door, police had set up a checkpoint to harass and intimidate staff. Pro-government paramilitary in civilian clothes menaced and monitored them, sometimes blocking their entry, she said.

When a colleague drove home, police repeatedly stopped him, pulled him out of his truck and delivered a message: Stop reporting.

They’d been reporting on street protests in April that year that began over proposed pension reform but soon exploded, tapping into long-simmering discontent with Ortega’s regime, the streets filling with the blue-and-white banners of the opposition.

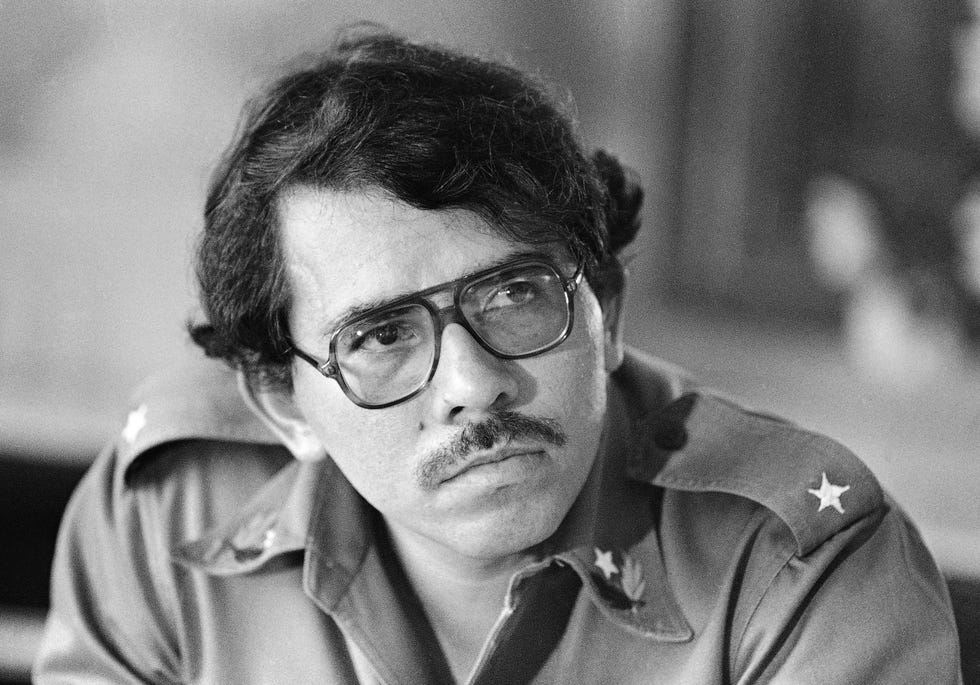

Since returning to presidency in 2007, Ortega had gained control of courts and the national assembly to allow him to stay in power in the nation of nearly 7 million, disillusioning some former Sandinistas as he grew more autocratic. He made his wife, Rosario Murillo, the vice president.

Ortega’s distrust and disdain of the press dated back decades. While some TV stations and newspapers were owned by Oretga allies, some journalists said, independent outlets often had to be cautious about directly criticizing the Ortega government.

When the protests threatened Ortega’s grip, Ortega framed them as an attempted coup and ramped up repression on demonstrators, civil society and independent or critical news outlets and reporters.

Attacks by police and pro-government paramilitary groups in civilian clothing left more than 300 dead and thousands injured, according to Human Rights Watch. Hundreds of political prisoners were jailed. A United Nations report found there were extrajudicial killings, arbitrary detentions and torture. Ortega denied the allegations.

When protests began, the government ordered cable providers to cut the signals of at least five TV channels, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. By the end of the year, the group documented attacks, arrests and surveillance of journalists.

Even as street protest subsided later in the year, the government’s crackdown on dissenting voices and independent media continued.

On the night of Dec. 21, Pineda was at her station when police stormed in.

“When the police entered the channel by force, I grabbed the microphone in master control and began to make a public complaint” on air, she said. She hid briefly under a set of stairs before she was taken to prison along with another station leader.

Inside her slimy concrete cell, which reeked of sweat and clogged toilets, authorities began “a tortuous process of interrogations and false accusation,” she said.

She believes guards put something in her food that made her dizzy and vomit. After 40 days, she was transferred to a women’s prison. “The lack of communication and isolation was terrible,” she said.

In June 2019, Pineda and station director Miguel Mora were among more than 100 political prisoners as part of an amnesty. According to The Guardian, opposition leaders said the measure would forgive abuses by police and pro-government militias.

She would denounce her detention “just for doing my job as a journalist.” She knew she couldn’t continue to do that work in Nicaragua.

Because her mother was from Costa Rica, she had dual citizenship, and was grateful to have relatives there. But she knew she was leaving behind many friends and fellow journalists.

Two days after being freed from prison, Pineda and her mother packed up and crossed the border.

After demonstrations are crushed, a new wave of repression

Carlos Chamorro, the editor of the news outlet Confidencial and a member of a prominent family long involved with Nicaraguan media and politics, was familiar with the dangers.

His father was the publisher of the country’s oldest newspaper, La Prensa. It had been critical of the Somoza family regime, whose repressive rule lasted for more than 40 years.

In the 1970s, to overcome censorship, journalists would read independent news aloud from church atriums and pulpits, in a tradition dubbed “catacomb journalism.”

In 1978, Chamorro’s father was assassinated, fueling government opposition.

The following year, the Somoza regime was ousted by the socialist Sandinista National Liberation Front, of which Ortega was a leader.

During the 1980s, amid the fight with U.S.-backed Contra rebels, the paper grew critical of the Sandinista government and its economic policies – drawing attacks, accusations of publishing U.S. propaganda and periods of censorship.

More than three decades later, following the 2018 demonstrations, it was Ortega who was blocking ink and paper for La Prensa and another national daily newspaper, El Nuevo Diario, which was forced to close in 2019. For a time, La Prensa was the last remaining national daily print newspaper. A January 2020 editorial in La Prensa was headlined,“The Dictatorship strangles La Prensa.”

That same year, Nicaragua approved its “Special Law on Cyber Crimes,” threatening prison for spreading information deemed false, capable of spreading alarm or putting national sovereignty at risk.

By 2021, La Prensa’s publisher, Juan Lorenzo Holmann, was imprisoned on charges of money laundering. Its equipment was confiscated. La Prensa, forced to drop its print edition, moved its entire operation outside of the country the following year. At that time, there was not a single newspaper in print.

Chamorro, who led the news outlet Confidencial, had fled once, after his offices were taken over by police in late 2018. But he returned and created a temporary newsroom.

In 2021, ahead of elections, Ortega launched a renewed wave of repression, arresting potential presidential contenders. More than 1,000 civil society organizations were shut down over time.

In May that year, Chamorro said, police once again raided Confidencial’s offices, seizing computers and equipment. When he learned he could face criminal charges, he left for Costa Rica with his wife. He crossed the border at a “blind spot,” he said.

Five days later, he said, police raided the home he left behind.

“It is very difficult. It’s something you don’t plan. You don’t want to leave. You’re not a criminal. You’re just doing journalism,” he said. “Exile is painful. At the same time, it’s the only alternative to continue being a journalist.”

That same year, Arce, the 32-year-old journalist, had to make a similar decision.

Arce had been attacked while live-streaming protests and fled, but had returned to start a new investigative digital site called Divergentes. Then he got a tip from a source that it wasn’t safe to remain in the country.

The next morning, he says, he put a pair of pants, two T-shirts, socks and his allergy medication into a backpack and slipped across the border where no one could see him.

“Gone was my house, my family, my dog, my friends, my routines and everything I had built for 30 years,” he told USA TODAY.

The challenges of reporting in exile

At home in Costa Rica, Pineda gets up every day at 5 a.m. She reads the news on her phone and plans story assignments for the now-digital 100% Noticias.

After coffee, eggs and a rice-and-bean dish called gallo pinto, she’s juggling all day: Talking to sources, conferring with staff, preparing for an interview show, checking website metrics and shepherding stories that recently included updates on political prisoners and government conflicts with the Catholic Church.

“Exile is hard” for many reasons, she said. One is that it makes the job exponentially more difficult.

Sources are hard to cultivate back home. No one wants to go on the record, afraid of prosecution. Anonymous information means more meticulous vetting and confirmation. Photos have to be pulled from social media.

“It’s three times as difficult,” Arce said, who now operates Divergentes from San Jose.

Some exiled journalists in Costa Rica still direct a group of clandestine reporters back home. In May, Nicaraguan police arrested a freelance reporter who contributed to Nicaraguan outlets operating in exile, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Few if any of the roughly 25 Nicaraguan outlets that have relocated to Costa Rica – including La Prensa, Confidencial, 100% Noticias and Divergentes, – can afford offices for traditional newsrooms. Reporters and editors work from their apartments.

Over at Confidencial, the collapse of Nicaraguan advertising means relying on grants, audience contributions and video monetization to pay its 15-member staff, Chamorro said. Pineda, too, says she’s always hunting for donations to help keep her outlet afloat.

Also struggling are many reporters, who often arrive in Costa Rica with few resources as they seek immigration status and work permits in a country with a higher cost of living.

“There are many fellow journalists who cross the border with only their clothes on,” Arce said. “Some still have jobs in the media they work in, but others don’t. And it’s more difficult for those. Many colleagues have slept on the streets and survived on charity.”

Marcos Barquero, of Costa Rica’s Institute for Press and Freedom of Expression, helps provide $500 cash assistance for three months for food, medicine and clothing. He said many working in media have extra jobs – from selling food to providing child care.

Others have left the profession for better-paying fields or because they are afraid that relatives back in Nicaragua will face threats for their work.

Octavio Enríquez, an investigative reporter with Confidencial and a member of Connectas, a nonprofit journalism initiative, also left Nicaragua to continue reporting.

But his work continued from Costa Rica, a story related to government corruption led to threats against his family – forcing his wife and children to join him. He still hasn’t been able to visit the grave of his brother who died after he left.

“Journalism saved me throughout this crisis and I cling to continue doing so, even though adversity is growing,” he said. “There is a crusade by authoritarian leaders against independent journalism. Regardless of ideologies, they have criminalized journalism, because it exposes its true face to the population. This is what is happening in all of Central America.”

He and others point to El Salvador, where an El Faro editorial said it had faced fabricated criminal accusations, physical surveillance and threats, spyware attacks, harassment of advertisers and defamation from public officials. The administration of Nayib Bukele has denied using spyware to monitor journalists.

In neighboring Guatemala, where a pro-democracy reformer candidate is seeking a the presidency in upcoming run-off election, a 2022 US Embassy report found that increasing ‘Intimidation of journalists had fueled struggles and “significant self-censorship.”

Marielos Monzón, a 52-year-old Guatemalan journalist and member of the Network of Central American Journalists, said 22 journalists fled the country in the last year.

“Every time you go to write a story in which power groups are involved, you think, “Can they put me in jail for writing this, for doing my job?” she told USA Today.

And even though Costa Rica remains a relative oasis, this year Reporters Without Borders downgraded the country’s press freedom rating citing government verbal attacks and instances of refusing to provide public interest information.

President Rodrigo Chaves Robles, during his campaign leading to his 2022 election, promised to retaliate against publications that reported critically on his past, according to NBC. He has said press freedoms remain healthy, but has described the country’s media as “rats.”

The journalists in exile from Nicaragua say they’re not giving up – much like their predecessors in the 1970s.

These days, they have a new kind of catacomb journalism.

About half of Confidential’s web audience live in Nicaragua, still able to access it via the internet. Two former broadcast news programs, now banned on television, now reach more than 415,000 subscribers through YouTube and Facebook, Chamorro said during a recent lecture.

Divergentes and others are using similar tools to provide independent news reporters can’t produce inside the country.

“The media that have survived in exile continue to reach Nicaraguans within the country, mainly in urban and semi-urban areas with Internet access,” Arce said. “But in rural locations, the reach is more complicated.”

Some reporters struggling in Costa Rica wonder why they still do the work and lament the impact their work has had on their families. Arce said it’s easy to fall into depression, missing his home and country.

But in the end, Pineda – whose work days often last 11 p.m. – remains “married” to the work and more determined than ever, she said.

In February, Ortega’s regime unexpectedly deported 222 political prisoners including political leaders, priests, students, activists and journalists to the United States. Ortega called them “terrorists,” and Nicaraguan lawmakers allowed them to be stripped of their citizenship.

Pineda hopes the international community pays more attention to growing media repression as a harbinger of eroding democracy and increased political instability – a problem that can impact economic and migration trends far beyond a nation’s borders.

“Nicaragua is a mirror of what can happen in other countries – and is happening,” Pineda said.