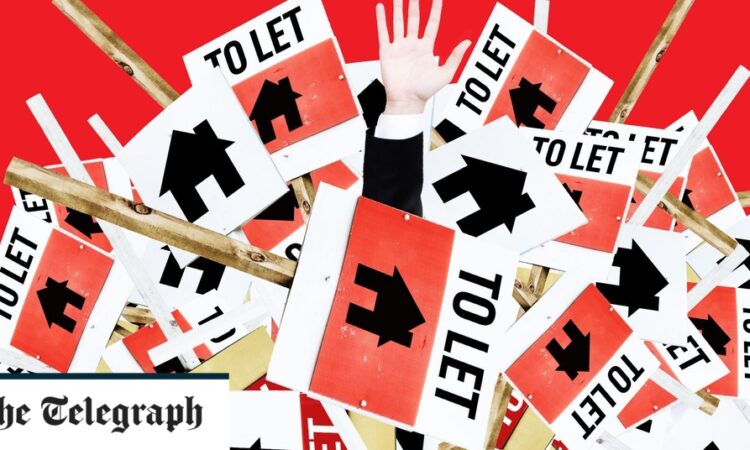

The picture that’s emerging is of a broken system in which everyone is hurting – landlords and tenants alike. The rental market is another brick in the teetering Jenga tower that the UK property market has come to resemble; landlords are the keystones on which so much of the edifice rests. What happens if they are removed?

We may soon find out. Sue Hull has spent almost three decades building up a small buy-to-let portfolio, which she hoped would support her into old age. Today, she is considering dismantling her little empire of houses in Essex and Sussex, because the numbers no longer stack up. “I don’t want to sell; I have to,” says Hull, 49. “I actually love being a landlord, giving a home to families and seeing their children grow up, but I got into this business to make a profit, not just to scrape by.”

Hull, a personal trainer who lives in Bexhill-on-Sea in East Sussex, was in her 20s when she bought her first rental property. “Buy-to-let was just starting to boom and I thought: ‘I want in’.” She saved up for a deposit and, in the mid-1990s, spent £48,000 on a two-bedroom flat in Colchester, Essex, where she was living at the time. Over the years she decided that houses were a better bet than leasehold flats with their management charges and high maintenance costs. Her portfolio now comprises two three-bedroom houses in Essex and six similar properties in Eastbourne, East Sussex.

When she began renting properties, Hull earned a yield of around 8 per cent. Over the years that has fallen to 6 per cent or 5 per cent. And, as her fixed-rate mortgages start to expire, her yields look set to drop below what she could earn if she just parked her money in a high street bank. The first mortgage, on one of the Eastbourne houses, runs out in September. Hull is currently paying 2.19 per cent. The best new deal she has been able to find is a two-year fix at 5.13 per cent.

“And I would have to pay a £5,000 arrangement fee,” she says. “My repayments will go up two-and-a-half times.” Hull anticipates the yield on the property dropping from 6.4 per cent to 3.7 per cent – and on that basis keeping the house on will be unsustainable. “I can’t just put the rent up – people can’t afford it,” says Hull.

She’s almost certainly right. According to Hamptons, a typical landlord refinancing a 2.2 per cent two-year fixed rate mortgage at 6 per cent would need to raise rents by 31 per cent. Even in a red-hot rental market, that’s unlikely to be doable. There are 5.5 million private rental homes in the UK and a third of these households already spend at least half of their take-home pay on rent.

The cracks in this segment of the property market are becoming hard to ignore. Buy-to-let mortgages in arrears are increasing at a faster rate than residential mortgages – up 16 per cent in the first three months of the year compared with the past three months of 2022 (albeit off a reasonably low base), according to UK Finance.

As a cohort, landlords are more exposed to rate rises than residential mortgage holders. There are a shade more than 8.5 million mortgages outstanding in the UK, according to UK Finance. Of these, 81 per cent are fixed, 9 per cent are on a standard variable rate, and 8 per cent are trackers.

Conversely, there are just over two million buy-to-let mortgages. Of these, only 66 per cent are fixed, 18 per cent are on standard variable rates, and 14 per cent are trackers. According to the Bank figures this week, if landlords were to absorb higher mortgage costs themselves, the share of buy-to-let mortgages with interest coverage ratios (the measure of rental income relative to interest payments) below 125 per cent would increase from 3 per cent at the end of last year to more than 40 per cent by the end of 2025.

There are doubtless some landlords exploiting the febrile climate to push through absurd rent increases. Despite its leaky roof, rotting beams, and a general air of decay, James Frater considered his flat share a fairly good deal – by London standards at least – at £800 a month. That was until the estate agent who manages the property hit him and his two flatmates with a bombshell.

“We had been paying probably slightly below market rates given the state of it, but in February the estate agent told us the landlord wanted to put it up to £1,150 – that is a more than 40 per cent increase,” says Frater. “I was furious that a landlord could leave us with a hole in the roof, beams that are rotting, a roof that is sagging, a dishwasher that didn’t work, and then hike the rent like this.”