Nonprofit near Kansas City seeks to become ‘epicenter of the school-choice movement’ • Missouri Independent

The headquarters of the Herzog Foundation sits on the edge of Smithville, in an 18,000-square-foot stone and glass building on a corner lot across the street from a cornfield on a gravel-lined highway.

Few Missouians have likely heard of the Stanley M. Herzog Charitable Foundation, or the organization’s namesake. But the unassuming locale masks what has been described as the “epicenter of the school-choice movement.”

Stan Herzog’s political largesse bankrolled a generation of conservative candidates and causes in Missouri, pouring through a constellation of political action committees and nonprofits. When he died in 2019, he set aside $300 million to start a foundation dedicated to expanding the reach of Christian education.

That mission kicked into overdrive in 2021, when Missouri lawmakers created a tax credit to support scholarships to help low-income students and those with disabilities attend private schools. Since then, a subsidiary of the Herzog Foundation has distributed almost half of the scholarships in the state.

Let us know what you think…

And while the foundation thrives in Missouri, it also spreads its message nationwide.

It champions rallies across the country, holds workshops and bankrolls Christian-school-building packages. Former U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos spoke at the Herzog Foundation’s launch, and former U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo gave a presentation at the foundation’s headquarters this February.

The foundation is barred from direct electoral activity because it is a charity, but businesses and political entities connected to Herzog continue pouring money into campaigns — spending more than $3.6 million on campaigns for state office since Herzog’s 2019 death , according to Missouri Ethics Commission filings.

It’s a recipe that gives the Herzog Foundation considerable stature in Missouri politics, as the push to expand Herzog’s education agenda continues to pick up steam.

“As far as education goes in Republican Party politics, they’re one of the major influencers in the state,” said Jean Evans, American Federation for Children’s Missouri state lead.

“The Herzog family has been prolific donors to the Republican Party for a long time,” Evans added. “Stan Herzog passed away, but they’ve continued to support candidates and political causes. And now the Herzog Foundation is involved.”

But the foundation is not without its critics, who claim its real goal is the destruction of public education in Missouri and across the country.

“Herzog and other groups like Herzog have made it their goal to funnel money from taxpayers to private institutions,” said Rep. Maggie Nurrenbern, a Clay County Democrat who is running for a seat in the Missouri Senate.

“We’re going to continue to see more legislation pushed by groups like Herzog to dismantle public schools as we know them,” she said.

Legacy

Stan Herzog made his fortune running his late father’s railroad construction company — now run by a former state senator.

Herzog laid the groundwork for the Herzog Foundation in 2016, but it didn’t launch until after his death, when he set aside nearly $325 million for his mission, giving entrusted parties 20 years to spend his endowment.

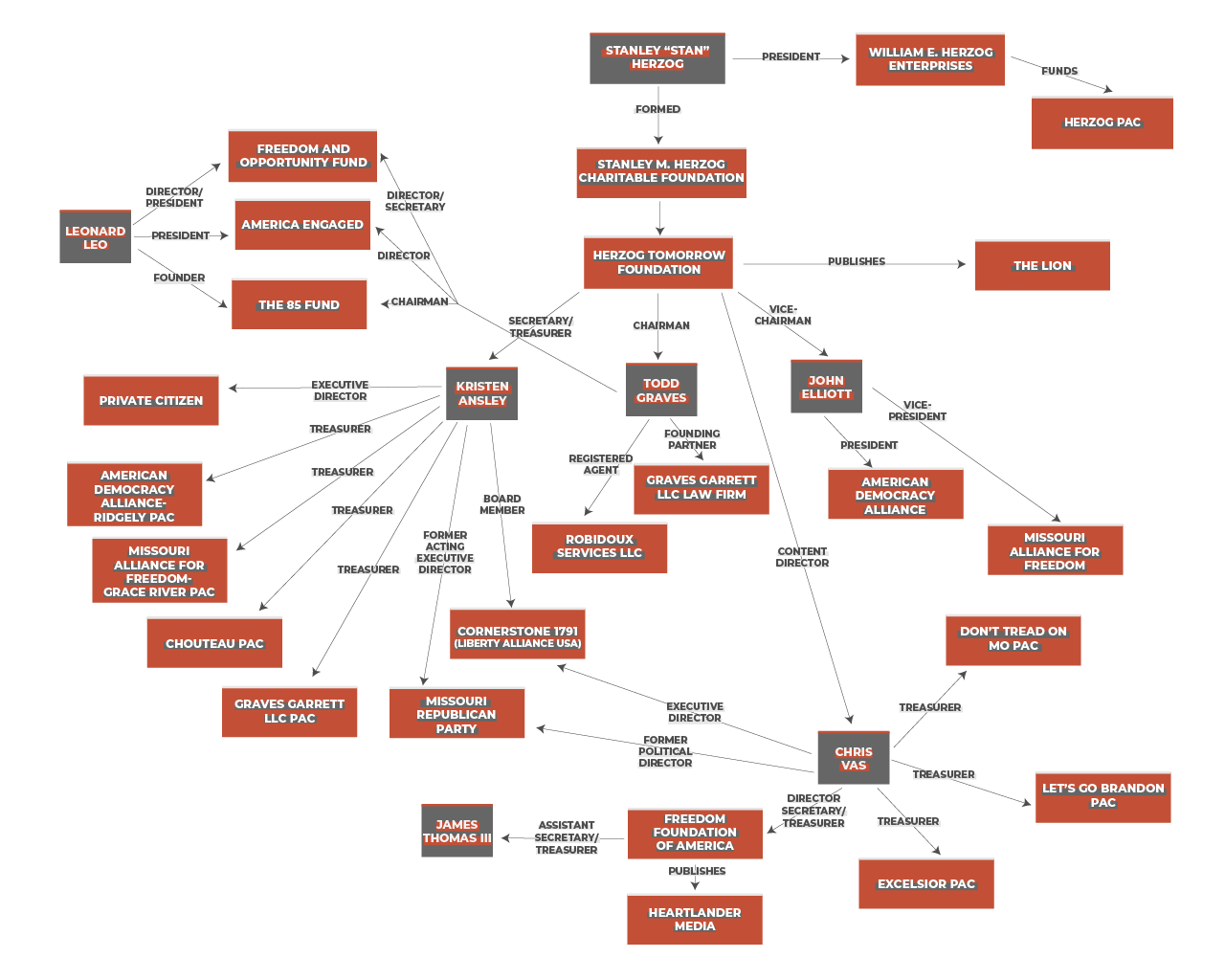

Leading the foundation is Todd Graves, a former U.S. attorney and chairman of the Missouri Republican Party whose brother is U.S. Rep. Sam Graves.

Kristen Blanchard Ansley is the secretary and treasurer. She is a former executive director of the Missouri Republican Party, and over the years has been involved in numerous PACs and nonprofits that poured Herzog’s money into state and local campaigns.

John Elliott is vice chairman. He also is connected to several political nonprofits that have been prolific donors in Missouri politics for years.

In December 2021, the leaders of the Stanley M. Herzog Charitable Foundation established another nonprofit called the Herzog Tomorrow Foundation. It was created specifically to distribute tax dollars set aside by Missourians under the new scholarship program created by lawmakers.

The program works by allowing Missourians — both individuals and businesses — to donate to educational assistance organizations in return for a tax credit equal to the donation, as long as it’s 50% or less of their tax burden.

When the General Assembly passed legislation in 2021 to create the program, the fiscal note indicated that the tax credits would take up to $75 million from the state’s general revenue annually.

Herzog Tomorrow Foundation’s application to participate in the program says its goal is to “catalyze and accelerate the development of quality Christ-centered K-12 education.”

It is allowed to take a percentage of the scholarship funds to cover administrative costs: 10% of the first $250,000, 8% of the next $500,000 and 3% of funds raised thereafter.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX

But the administrative fees don’t appear to be the motivating factor for becoming an educational assistance organization. According to Chris Vas, scholarship director at Herzog Tomorrow Foundation, the organization donated $800,000 back to the program “to ensure that every eligible student who applied for a scholarship received one.”

The Missouri Treasurer oversees the educational assistance organizations.

When the Herzog Tomorrow Foundation applied, now-State Auditor Scott Fitzpatrick was serving as treasurer. Fitzpatrick’s office told The Independent all applicants were scored using the same system, and every organization that applied were deemed eligible.

The Treasurer’s office has room for 10 education assistance organizations, but only six organizations applied.

“Being a new program, it was hard to speculate how many (education assistance organizations) would apply for the first year,” the auditor’s office said in a written response to questions, speaking from their time in the treasurer’s office.

Of the 1,313 students with scholarships in the first year, Herzog Tomorrow Foundation handled 598 of them, according to the treasurer’s office.

Vas testified in a House committee hearing in March that the foundation raised $3.1 million from 165 donors.

He said 20% of scholarship recipients had an individualized education plan, an accommodation plan and set of goals for students with disabilities. An additional 60% qualified for free or reduced lunch, and the rest were from families with incomes below 200% the free or reduced lunch threshold.

The foundation partnered with 80 schools statewide, of which 65 had a religious affiliation.

Influence

In the Stanley M. Herzog Charitable Foundation’s 2020 tax filing, the organization’s attorney stated that the foundation did not “attempt to influence any national, state or local legislation” and did not “participate or intervene in any political campaign.”

Vas said in an email that the foundation also “does not play any role in the legislative process.”

But while the foundation is prohibited from interfering in politics, Herzog’s money has long helped bankroll a web of politically active nonprofits and political action committees — most of which are tied to the foundation’s current leadership team.

Graves, in addition to being partner of a law firm that represented former Missouri Gov. Eric Greitens, Tea Party Patriots and witnesses in the federal January 6 probe, serves on three committees led by Leonard Leo, a Federalist Society co-chair that former president Donald Trump enlisted to help choose conservative judges.

Many of the political nonprofits and PACs funded with Herzog’s money list Graves’ law firm as their address.

Ansley is a board member of Cornerstone 1791, which also goes by “Liberty Alliance USA.” Vas serves as Cornerstone 1791’s executive director.

Cornerstone 1791 has spent a majority of its expenditures paying Robidoux Services LLC. In 2020, it spent nearly $250,000 for “management, operations and consulting services.”

Robidoux Services has no online presence. Graves is its registered agent, and its office is the Graves Garrett LLC office, according to the business’s paperwork. Vas did respond to a question asking what Robidoux Services is.

Other expenditures include a $1,105 contribution to “Don’t Tread on MO PAC,” a political action committee with Vas as treasurer, and $1,075 to “Excelsior PAC,” which Vas became treasurer of two years later.

In October 2022, Excelsior PAC spent $15,000 on mailers opposing state Rep. Ashley Aune. Axiom Strategies created the mailing, designing an image of Aune riding a bicycle with U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

“Radical liberal Ashley Aune wants to bring AOC-style politics to Jefferson City,” the postcard says.

Aune told The Independent her Clay County seat was eyed by Republicans as a district that could turn red.

“I was really surprised because it was just so far-fetched and kind of funny,” she said, recalling when she saw the postcard. “It’s not lost on me that A.O.C. and I are two Hispanic-identifying women, and we were being demonized.”

Ansley, Vas and Elliot also sit on the board of the Missouri Alliance for Freedom, a political nonprofit that has spent $770,000 since 2017, and American Democracy Alliance, a nonprofit that mostly donates to other nonprofits connected to Herzog.

Last year, a political action committee called “Let’s Go Brandon” poured money into the county executive race in Jefferson County to defeat former state Sen. Paul Wieland.

Wieland had drawn the ire of Graves when he vocally opposed his nomination for the University of Missouri Board of Curators a year earlier. And the money Let’s Go Brandon spent attacking Wieland came from an attorney who has long been close to Graves named Michael Ketchmark and Herzog Contracting Corporation.

Vas served as treasurer of Let’s Go Brandon while also working as the Herzog Foundation’s content director. He did not answer The Independent’s question asking why his PAC campaigned against Wieland.

He is also treasurer of Don’t Tread on Missouri PAC and Excelsior PAC.

Herzog companies have contributed $2.16 million to Missouri committees since 2017, when the state established campaign contribution limits.

Three arms of Herzog’s operations — Herzog Contracting Corporation, Herzog Technologies Inc. and Herzog Railroad Services Inc. — donate simultaneously to multiple political action committees. The three-pronged approach ensures that the committees aren’t primarily funded by a single company — although the three businesses act in unison.

Missouri law presumes that contributions made to a candidate by a committee primarily funded by a single entity are given “with the intent to circumvent the limitations on contributions.”

Matt Vianello, an attorney with Arch City Lawyers who has advised clients on campaign finance, said the three Herzog companies appear to be separate entities by their Secretary of State filing.

“They’re separate entities,” Vianello said. “So then that begs the question: Did they do this in a manner to get around campaign finance? That gets to a question of intent.”

Prior to Missouri establishing contribution limits, Herzog companies donated generously directly to candidates. The companies gave Jay Ashcroft’s campaign $125,000 in 2016 and $650,000 to Eric Greitens, who was then running for governor.

Now, Herzog money flows through political action committees with the same few treasurers at the helm. These committees then contribute to similar sets of candidates and spread funds to more committees with similar donations, according to Missouri Ethics Commission filings.

Two committees, American Democracy Alliance-Ridgely PAC and Missouri Alliance for Freedom-Grace River PAC, have nearly identical contributions. Vas did not respond to a question about the PAC’s contributions.

Ansley is a treasurer or former treasurer of many committees receiving Herzog funds alongside Vas and attorney James C. Thomas III.

Vianello said donating through PACs isn’t illegal. It becomes a violation when donors use PACs to intentionally obscure campaign’s financiers or skirt campaign contribution limits.

“It just depends on the intent of the person or people, and it’s a difficult thing to know,” he said. “It’s a difficult thing to investigate.”

The Missouri Ethics Commission only investigates after it receives a complaint. So although the commission publishes the donation history of organizations, it doesn’t continually review the information unless flagged.

It also serves as an overseer for the General Assembly’s conflict-of-interest disclosures.

State Rep. Josh Hurlbert, R-Smithville, works as a scholarship coordinator for the Herzog Tomorrow Foundation. His LinkedIn profile says he began this position in May 2022. The most recent Missouri Ethics Commission (MEC) personal financial disclosure was due prior to him taking the role and does not include his position at the foundation.

More than half the bills he filed this legislative session are on the topic of the Missouri empowerment scholarship accounts. One of the bills, though, sought to scrap the use of EAOs as a scholarship middleman and establish a board with the Missouri Treasurer’s Office.

He has declined The Independent’s request for an interview and avoided other Missouri media outlets on the topic.

Rep. Paula Brown, D-Hazelwood, proposed a bill that would require legislators to disclose to the MEC when they file a bill that would benefit their employer. Inspired by Hurlbert, the bill was never assigned to committee.

Growth

At the end of 2021, the Herzog Foundation had nearly $364 million in assets, up $7.4 million from the previous year.

Although Stan Herzog gave 20 years to spend his endowment, investment income should sustain the foundation beyond that timeline.

With a resume of training events, awards, podcasts and speaker series — the foundation is likely expanding its programs.

The Herzog Tomorrow Foundation, the nonprofit that distributes Missourians’ tax dollars as an educational assistance organization, filed a business name with the secretary of state: “American Christian Education Alliance.”

In January, the nonprofit applied for two trademarks. The trademark registration is intended to cover “charitable fundraising” and “financial administration of education grant programs developed for students seeking a Christian education.”

Vas said ACE Alliance is a “project of the Herzog Tomorrow Foundation.”

“Its focus is to build a nationwide coalition of Christian education supporters,” he said.

Even before Missouri’s tax credit program was implemented, lawmakers were considering expanding it. While those efforts stalled, proponents are expected to try again when the legislature reconvenes in January.

“The MOScholars program has allowed low-income students and students with (individualized education plans) to attend the school of their dreams. We are extremely proud to participate in the program and help the next generation achieve the education that they deserve,” Vas said. “Our only hope is that we can help more kids in the future.”