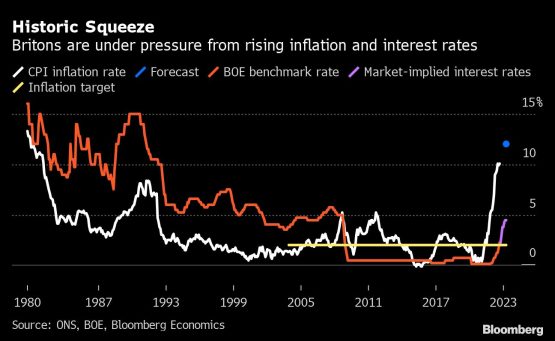

Britain’s economy is shuddering to a halt under the weight of the biggest increases in borrowing costs in more than three decades, with concern mounting that rates are headed higher still.

Economists and investors expect the UK central bank to raise its benchmark lending rate by three-quarters of a percentage point to 3% on November 3. That’s the highest since 2008 and would mark the biggest single increase in 33 years.

Households already are paying more for new mortgages, and businesses are complaining about the rising cost of credit. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s government is scrambling to cut spending after a surge in market interest rates sent its debt servicing costs soaring.

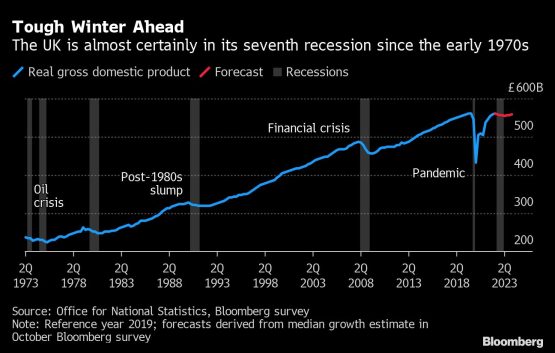

Together, those forces mean the UK probably has already entered a recession. And for the first time in decades, the Bank of England and Treasury are both slamming on the brakes in the face of economic weakness. They’re focusing on getting inflation under control after it leaped to a 40-year high, delivering a searing squeeze on living standards.

“We’re in for a fairly nasty recession,” said Innes McFee, managing director of Oxford Economics “The macro response is still set to tighten as we head into a very difficult winter.”

The current pace of monetary tightening ends more than a decade of cheap money, when the BOE pushed rates to near zero to pull the economy out of the global financial crisis and then the pandemic. It marks the biggest tightening cycle since the period from 1988 to 1990, which brought rates to a peak of 15%.

The BOE’s intention this time is to cool the economy enough that upward pressures on wages and prices dissipate. Inflation surged after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sent the cost of energy on an upward spiral in Europe, adding to lockdown-induced supply-chain disruption that boosted the cost of goods.

Even so, the impact that higher rates are having on the economy now explains why investors have started to pull back bets for the pace of hikes. Markets that once priced in a 2 percentage point hike this week now think the BOE’s decision is between a half-point and three-quarters. BOE Deputy Governor Ben Broadbent earlier this month warned rates probably won’t rise as much as investors expect.

Here’s how various parts of the economy are being affected:

Property market

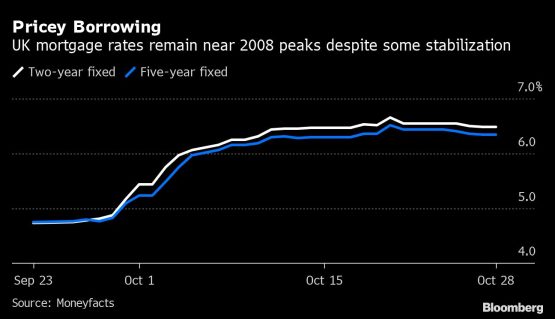

UK mortgage rates have surged close to peaks last seen in the 2008 financial crisis. Liz Truss roiled markets during her brief spell as prime minister with promises to boost borrowing and slash taxes, a package that since has been reversed after Sunak took over.

The cost of a two-year fixed-rate mortgage is now 6.48%, near the highest in 14 years and up from 2.34% in December, according to Moneyfacts Group Plc. At that price, those who borrow about £200,000 will spend at least £10,000 more over the course of two years than they would have at the end of last year.

Those figures will weigh on what buyers can afford in the housing market. Lloyds Banking Group Plc expects house prices to fall 7.9% next year and sees one scenario where the drop could be as sharp as 18%.

Analysts at Credit Suisse say that house prices “could easily fall 10% to 15,” and others including Niraj Shah of Bloomberg Economics predict double-digit declines. Analysts at HSBC have predicted falls of 7.5% nationally and 15% in London.

Small business

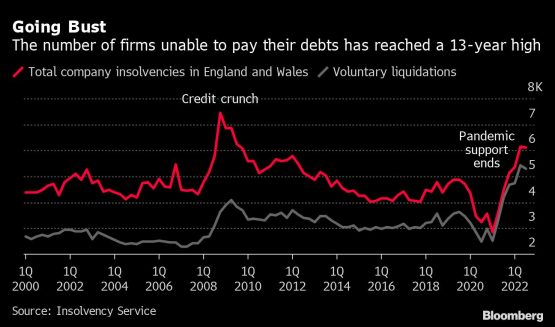

UK companies are having trouble with high interest rates, which come on top of a surge in inflation and energy costs.

About half of small and medium-sized businesses said the pricing and availability of loans was “poor” in the three months through September, according to a poll by the Federation of Small Businesses. That’s the lowest in seven years.

Some firms are priced out of investments they would’ve been eligible for just a few months ago. Kingdom Thenga, the owner of several hospitality businesses in the Chester area, saw borrowing costs more than double over last 12 to 18 months, forcing him to postpone a mortgage to buy a pub he’s currently leasing.

The worry is that many will be forced into insolvency if rates climb above 5%. Begbies Traynor, a consultancy, predicts more than 28,000 companies could go bust next year.

“We are now in an environment that we have not seen for many years, with a dangerous mix of rapidly rising inflation, escalating interest rates and crumbling consumer confidence,” said Julie Palmer, partner at Begbies Traynor.

Banks

For UK banks, higher rates are a mixed blessing. On the one hand, it translates into higher profits for their core lending businesses after years in which rock-bottom rates squeezed margins.

But higher borrowing costs are a “double-edged sword” since they also raise the risk of more loans souring and leaving banks on the hook for losses, said Fahed Kunwar, an analyst at Redburn. The inflationary environment makes costs far harder to control.

Third-quarter results from banks underlined the tightrope executives are facing. Net interest margins at Barclays Plc, Lloyds and NatWest Group Plc all rose, but so did impairments for potential losses.

Investors took particular fright at at a report from NatWest on Friday, which warned that “we no longer expect costs to be broadly stable given increased inflationary pressures.” Its shares fell as much as 9.7%.

Government borrowing

Soaring inflation is having an adverse effect on the public finances. That’s in large part because payments on around a quarter of government debt are linked to the Retail Prices Index, which is rising at an annual pace of almost 13% — the most in 41 years.

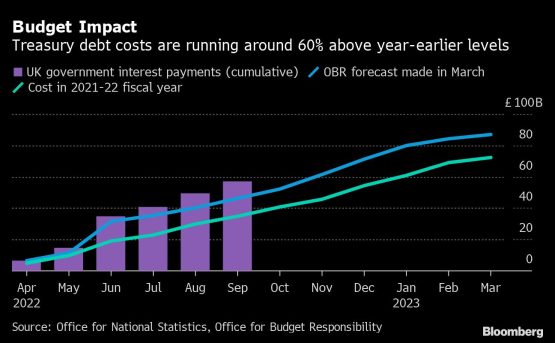

In the first six months of the fiscal year, the Treasury saw its debt-interest bill jump by 64% from a year earlier to £57.1 billion — significantly more than the country’s fiscal watchdog predicted in March.

It’s adding further pressure to a budget shortfall that’s already under strain from decisions to cut payroll taxes and stamp duty on property purchases, a weakening economy and the huge cost of helping households and businesses cope with their energy bills.

Sunak and Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt are working on plans to fill a £35 billion hole in the public finances with room to spare, which could entail tax rises and spending cuts totaling as much as £50 billion.

On current trends, the deficit for 2022-23 as a whole could reach as much as £170 billion, almost double the £99 billion predicted by the Office for Budget Responsibility in March.

© 2022 Bloomberg