Avinash Persaud and Barbados’s Mia Mottley Have an Ambitious Plan to Use International Capital to Fight Poverty

Avinash Persaud is impatient with his audience. “I was born into the moral imperative of development,” he tells diplomats gathered in March at the G-20 Sherpas Meeting in India. “My growing up was a realization that moral imperative is not enough.”

Development officials have descended on the lush coastal state of Kerala to discuss “woman-led development,” “bridging the digital divide,” and other subjects on which moral grandstanding is endemic.

Persaud seems short-tempered. He rushes through a flat personal introduction and moves on to the proposal he was invited to discuss: a plan to lower the cost of borrowing for green investment in poor countries. India, this year’s G-20 president, has asked this statesman from a tiny Caribbean island to give the keynote address.

Since 2020, Persaud, who is climate envoy to Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley, has vaulted to prominence in the small and sharp-elbowed world of development finance, advising big industrializing economies such as Brazil and Pakistan. His warm reception in India is partly due to the lectures he won’t deliver. He is trying fix a lopsided global financial system, not nagging anyone to shut off coal.

A London banker of Caribbean Indian descent, Persaud has been friends with Mottley since their days as students at the London School of Economics. He led currencies research at State Street and J.P. Morgan, where he developed trading strategies based on the observation that currency fluctuations are often more tied to investor risk appetite and U.S. interest rates than the soundness of developing economies.

The COVID-19 pandemic and its aftershocks are the latest evidence of that dynamic. Rich countries spent heavily to ride out the crisis. As their economies kicked back into gear, central banks raised rates, hiking the cost of borrowing in global bond markets.

Great powers’ pullback also deepened the distress. This year marks the 200th anniversary of the Monroe Doctrine, yet the United States is nowhere to be found in the Caribbean. China has pared back its 2008-2018 spree of overseas development finance. Capital for green infrastructure in the global south has abruptly dried up.

In 2007, Persaud moved back to Barbados and began working with Mottley, then the minister of economic affairs and development. As government official in a developing country, he learned to be a generalist: stepping in to save a flailing Four Seasons, leading negotiations on a new airport, litigating fights over a local appellation for rum producers.

The current global debt crisis is Persaud’s big moment. The reform agenda he has designed with Mottley, the Bridgetown Initiative, aims to reform international financial flows to help poor countries spend countercyclically during market contractions and industrialize without destroying the planet. And he’s winning backers in the West.

French President Emmanuel Macron welcomes Mia Mottley, the prime minister of Barbados, before a meeting in Paris on March 10. Christophe Archambault/AFP via Getty Images

“These developed country kids are gluing themselves to the road on climate change. They’re not gluing themselves to the road on water scarcity, on development, on gender violence,” he told Indian civil society representatives on a panel in March. “Windows are opening. Money is being offered on climate.”

French President Emmanuel Macron, facing domestic backlash to spending cuts and seeking a progressive win, has invited Mottley to headline a summit next week that is also expected to feature German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, top Indian officials, and other developing world diplomats.

As a banker turned green developmentalist, Persaud is testing the limits of what can be accomplished within the existing financial architecture. Publicly recalcitrant officials in the U.S. Treasury Department have praised the agenda, and European countries have scrambled to be included.

Yet as he attempts to use the global shocks of the 2020s to his advantage, Persaud is also their captive: an embattled internationalist attempting to work through multilateral institutions with shrinking clout, promoting global public goods in a world increasingly fragmenting into rival blocs.

Boats float offshore in Bridgetown, Barbados, on Nov. 17, 2021.Joe Raedle/Getty Images

I visited Persaud in January at his hilltop home in the parish of Saint Michael, where a troop of green monkeys roams the lawn. Persaud has split from his ex-wife and entertains late into the evening, playing an eclectic mix of hits by Cesária Évora, Eurythmics, and Burna Boy.

Friends drift in and out. Mostly women, they are bubbly entertainers and entrepreneurs: an actor, a cricket commentator, a publicist. Persaud has avoided the cynical academics and armchair liberals who made up his social circle in London. He moved back to the island expecting to make cosmopolitan friends, reasoning that a micronation must be open to the world. Instead, he says he has encountered an “insular” elite.

The easternmost island in the West Indies, Barbados is a relatively affluent developing country, with revenues from offshore banking and tourism. It rivals oil-exporting neighbor Trinidad and Tobago in per capita income, though the two former British colonies are otherwise like chalk and cheese.

Trinidad, where Persaud’s mother was born, pummels the senses. The street food scene remixes classics from the island’s many ethnic groups, which include people of African, Indian, Chinese, and European descent. The surf is choppy, so beachgoers hang back onshore and eat shark meat with hot chutney. Political rhetoric is endless banter, or picong, from the French piquant, for “sharp.”

Barbados is more soft-spoken and less diverse, a majority Black and overwhelmingly Christian country with milder food and scrupulously clean boardwalks. The seas are turquoise and tranquil as bathwater. But warming ocean temperatures and agricultural runoff have bred huge blooms of sargassum algae and killed off coral reefs that once fringed the island.

Government meetings in Barbados often open with a prayer. If political life can feel inhibited, it is also stable. Unlike Puerto Rico, where hotels are preying on a debt-distressed government to snap up prime waterfront land, there is little threat that Barbados’s beaches will fall into private control. Yet affluent citizens are keen to take up the cause anyway.

On one occasion that Persaud likes to recount, trash cans were left out on a beach overnight. A rumor circulated that the neighboring business was making a bid for privatization. Protesters poured out of their homes and took to the streets. “Maybe they’re Trotskyists and they believe in the continuous revolution—they believe it’s always under threat, and they must fight,” Persaud laughs. The eagerness to militate against such a far-fetched change is emblematic of a political class that he believes fears nothing so much as freshly poured concrete.

Persaud complains that his friends are part of the island’s “anti-growth coalition,” with a stake in the idling status quo. He wants to promote development that would push up wages and make his neighbors less able to afford their gardeners and domestic help.

One source of investment that has broken in is China. Barbados accepted Chinese Belt and Road lending in 2019, and Chinese migrant workers have been coming to the island for much longer. Pressed on the choice by a BBC news host, Mottley quoted the country’s first prime minister, who said Barbados should be “friends of all and satellites of none.”

Three men harvest sugar cane at a plantation in Barbados in 1965.Bristol Archives/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Persaud’s ancestors came to the Caribbean from India as indentured laborers. After the slave revolts of the early 1800s, colonial sugar planters hunted for a new supply of workers to take on the crushing demands of sugar cultivation. In 1837, John Gladstone, a plantation owner in British Guiana and the father of liberal British Prime Minister William Gladstone, proposed importing laborers from India. Hundreds of thousands were lured to the West Indies in the following decades.

Persaud’s father, the economist Bishnodat “Vishnu” Persaud, was the son of a Guyanese rice miller who went into debt and died young after a collapse in rice prices linked to the Great Depression. “Dad’s memory was of a man shaking with nervousness about each crop,” the younger Persaud recalled.

Vishnu left Guyana for the United Kingdom in the early 1950s and became a bus conductor. He might have stayed in that job, but the local shop steward with the Transport and General Workers’ Union noticed that he was bright and told him to attend college. Vishnu found his way to Queen’s University Belfast, where he studied economics, one of the few courses that did not require A-Level exams.

After earning his doctorate, Vishnu married a classmate and moved to Guyana. When race riots swept the country, they fled to Barbados, where Avinash Persaud was born. The family soon returned to London, where Vishnu joined the Commonwealth Secretariat and advised future Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, then the secretary-general of the South Commission.

It was a period of greater solidarity among developing countries—and a time when south-south cooperation commanded nervous attention in Washington. Jamaica’s Michael Manley had joined Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere in the Non-Aligned Movement, which refused to pick sides in the Cold War.

Vishnu often challenged the bloc’s faith in state-driven industrialization strategies, particularly for regions such as the Caribbean, which he doubted could be retooled for intensive factory output. (He described himself, another economist recalled, as the “loyal opposition” to the Washington Consensus). Avinash Persaud remembers long debates in his family home between his father and Singh—“a very unreconstructed Nehru socialist”—whom Vishnu gradually prodded to support liberalization.

As the head of the economic affairs division of the secretariat, Vishnu led the design of sanctions on South Africa in the 1980s. Responding to mounting international pressure, the apartheid regime in Pretoria embarked on a vast build-out of coal-fired generation—infrastructure that haunts it today—even feverishly developing a complex to produce oil from coal, in a bid to become resilient to oil embargoes.

Vishnu’s office at the secretariat was the converted living room of Carlton House Terrace, the former residence of the viceroy of India and of Prime Minister Gladstone, whose family had played a role in sending his ancestors to Guyana. In a karmic twist, Vishnu penned sanctions against South Africa from beneath a portrait of Gladstone, which hung over the mantlepiece.

Persaud during his time as an analyst with State Street Bank and Trust Company in London in October 2001.Alamy Images

Avinash Persaud graduated from the London School of Economics in 1988, determined not to join a bank financing apartheid. He was hired to analyze gilts at Phillips & Drew, which was promptly acquired, to his chagrin, by the Swiss bank UBS, which was then heavily linked to Pretoria.

After a stint at UBS, he went on to lead currencies research at J.P. Morgan, a role in which he spoke daily with bank economists stationed around the world. Each one would make a case for how the local currency would move based on economic fundamentals, such as recent institutional reforms or demand for a key commodity.

But currency markets didn’t seem to notice those fundamental shifts. On Mondays, Persaud would check the previous week’s market performance. If the Mexican peso was up, he noticed, currencies in Poland, Turkey, and Thailand probably were too, even though those assets shared few fundamental traits. If Mexico was doing poorly, so were the rest.

As an economics student, Persaud had been taught that individual investors had fixed appetites for risk—some shy, some adventurous. Instead, he found, investors moved as a herd, developing a shared perception of whether a country or asset was risky. What fluctuated was their tolerance for that risk. Sometimes they all became risk-lovers and flooded into emerging markets. Soon enough, they would retreat in unison. Economic reforms were not futile, but there was a long lag before they fed into debt and asset prices.

Yet the International Monetary Fund (IMF) scolded poor countries about their weak institutions, ignoring the global financial cycle. The lectures continued as morale deteriorated. Debt crises rattled emerging markets through the 1990s. Persaud began to see the world as divided into safe and risky assets.

To describe these dynamics more systematically, Persaud built J.P. Morgan’s “Event Risk Indicator,” an algorithm rating the likelihood of a currency crash by tracking investor risk appetite. His tool predicted every East Asian crash in 1997, he told the New York Times, except one in the Philippines.

The test for the indicator came in April 1998, when it blared red on Russia. Following the Asian financial crisis, risk appetite was drying up. Persaud’s rating system assigned the ruble a 99.1 percent chance of dropping by more than 10 percent that month, a prediction that was immediately picked up in the business press.

Sandy Warner, the J.P. Morgan chairman, rang up Persaud at his desk. The Russian finance minister had just been in his office, threatening to cancel their next transaction, Persaud remembers his boss saying. Warner told the young analyst that he had defended the independence of the research department, and hung up.

Persaud was briefly happy that his chairman had stood up for him, and then second-guessed himself. His tool might lose the bank millions in fees. How sure was he about the indicator? Had he become overly convinced of the importance of risk-on, risk-off dynamics?

“I’d gone to this peak view of, ‘No country’s fundamentals matter,’” Persaud said. Nervous about costing the bank more fees and suddenly doubting the overriding significance of investor mood, Persaud pulled Russia off the indicator. It had always been a bad candidate, he told himself, since Russia was “too nuclear to fail.” Rich countries wouldn’t allow it to default—it would be too catastrophic.

Four months later, Russia defaulted. It was a belated vindication of Persaud’s “peak macro” assumptions. The following year, the Financial Times’s Alan Beattie profiled him as the lead thinker behind the so-called New School of financial market analysis, which tracked investors’ frame of mind.

Overconfident risk exposure models pioneered by banks including J.P. Morgan also aggravated financial contagion, forcing traders to sell off even when they would have preferred to hold. In May 1998, with the Asian financial crisis in full swing, Persaud’s trip to Jakarta was cancelled due to rioting.

“Students have been killed, and women raped. Regional currencies are in free fall. Local equity markets are imploding,” Persaud later recalled of his time stuck in Singapore, in a note he sent to friends. “The really puzzling thing for an economist like myself was that, late at night over cold Tiger Beers on Boat Quay, the exhausted sellers I spoke to were not motivated by a downgrading of the long-run value of their assets. They were selling because their risk models were flashing red.”

“Value-at-risk” models claimed to track exposure to losses across a bank’s portfolio at any given moment, based on short-term price data. They had so impressed regulators that they were incorporated into the Basel bank supervision accord. But, Persaud showed in a paper published in 2000, they mistakenly assumed that traders acted independently of each other. In fact, when one bank attempted to reduce volatility, others followed suit, turning price declines into deadly spirals.

The insight would prove useful in the global financial crisis of 2008, when Persaud worked with the regulator Lord Adair Turner on macro-prudential rules to curb herd behavior in markets. Like Persaud, Turner now works on another source of fat-tail, highly correlated risk: climate change.

“Risk models such as value-at-risk tend to assume everything follows a probabilistically normal distribution, and you can infer the probability distribution of the future from the past,” Turner told Foreign Policy. “Both Avi and I realized that that is broadly nonsense.”

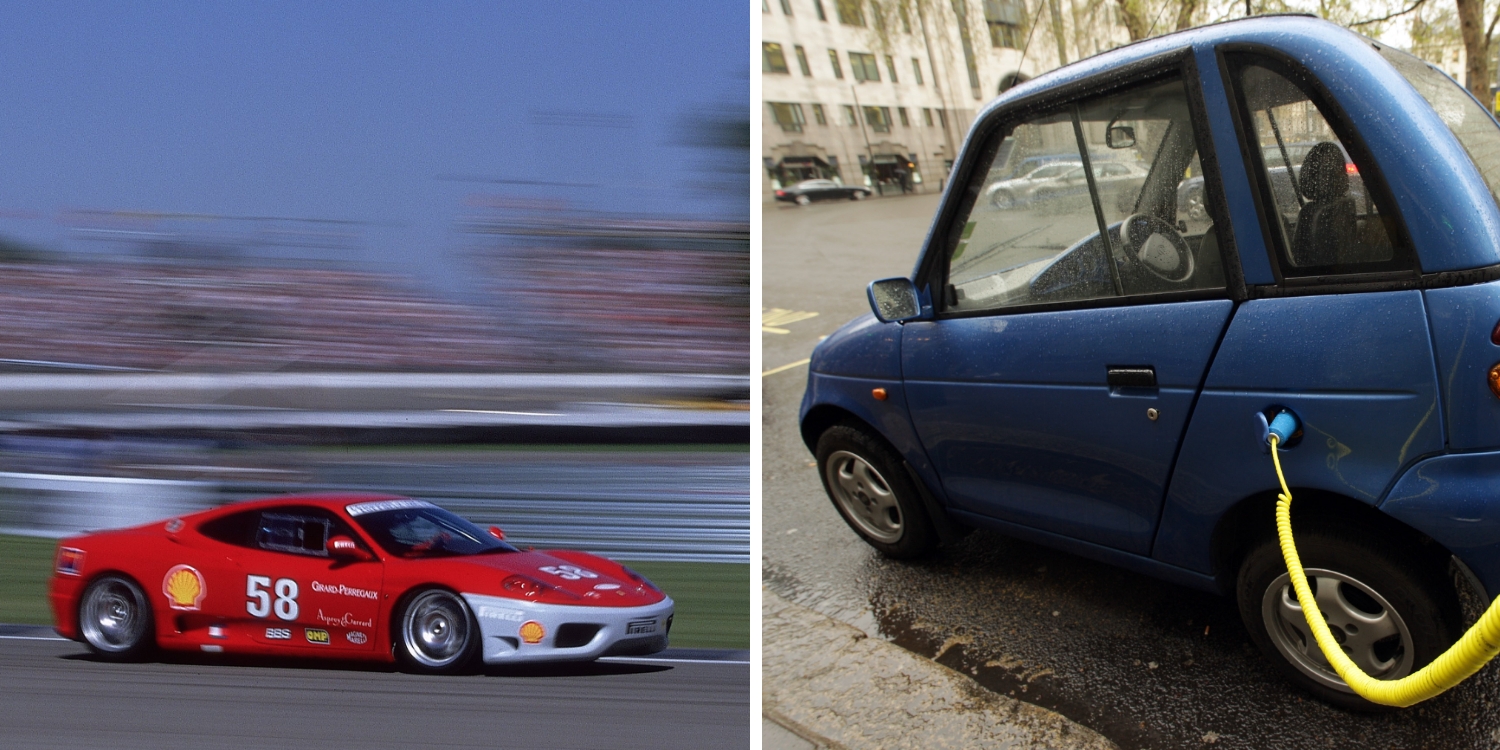

Persaud’s car evolution from the Ferrari 360 Modena to the electric G-Wiz.Getty Images

While at J.P. Morgan, Persaud drove a Ferrari 360 Modena, an unusually flashy choice for a member of the bank’s research department. It proved useful when he rushed his wife Ingrid, a conceptual artist and novelist, to the hospital to give birth to their twin boys. But one day, it occurred to him that the showy car mostly drew admiring glances from 12-year-old boys.

He decided to give up the coupe, and he found that he could only part with it by finding a radical alternative. He chose the G-Wiz, an Indian-produced electric car that did not even qualify as a highway-capable motor vehicle, only as a “heavy quadricycle.”

Persaud likewise switched from banking to public policy when he reconsidered whom he wanted to impress. In 2004, the anti-poverty campaigner David Hillman was preparing to launch a campaign for a financial transactions tax, or “Tobin tax,” a fractional levy on securities trading. He invited Persaud to an event promoting the tax.

Persaud showed up, but he didn’t express much enthusiasm, Hillman told Foreign Policy, until he got into a heated argument with Shriti Vadera, a former UBS banker who then worked at the British Treasury and would go on to become a top advisor to former Prime Minister Gordon Brown. Vadera explained that the Tobin tax was a noble but unworkable idea, Hillman said, since it was impossible to track, let alone tax, financial flows. Charged even a fraction of a cent, many argued at the time, capital would flee into cyberspace.

A spokesperson for Prudential, where Vadera is now the chair, disputed that recollection. He said Vadera “had to represent” the views of the Treasury, which was opposed to a unilateral Tobin tax on the view that trading would move elsewhere. “Treasury, including her, were clear they would support it if it was multilaterally imposed by major capital market centres,” he wrote.

As Hillman remembers it, Persaud was not sold on the Tobin tax, but he was indignant at the suggestion that markets would resist such a minor attempt at regulation. “The idea that bankers are so impotent as to be unable to do this struck him as laughably wrong,” Hillman said. “He went into that meeting curious and came out seriously wanting to fight.”

When Persaud thought back to the documents he had signed when he became a director at State Street, it seemed obvious that financiers could supervise capital. “I had to sign away my life and report that I understand every transaction we’ve ever done, that I know exactly who the customers were and vouch for them,” he said, “and I think, hang on, maybe finance isn’t all in cyberspace.”

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi speaks to victorious party workers at the Bharatiya Janata Party headquarters in New Delhi on May 23, 2019. Atul Loke/Getty Images

Frustration with the complacency of liberal elites runs through much of Persaud’s work. Even as he drew closer to English economists such as Turner and Charles Goodhart, he became obsessed with the rise of India, accepting a post as chairman of Elara Capital, an investment bank closely linked to billionaire Gautam Adani, who recently faced allegations of fraud.

Persaud is bullish on the growth of his ancestral home, though he is quick to admit his inexpert grasp of Indian politics. Unlike most intellectuals on the political left, Persaud does not wince at the mention of the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) or its leadership. While the Hindu nationalism of Prime Minister Narendra Modi troubles him, Persaud says the regime should be criticized for its substance, not its style.

In his telling, India’s moderate Congress party was too genteel, too comfortable, and for all its liberal pleasantries, too ready to accept sluggish growth in a country with sprawling poverty. “For Congress to appeal to the poor of India, they can’t just be secularists—they have to make themselves relevant. The BJP has done that,” Persaud said.

Persaud is similarly unconvinced by the White House’s happy talk about renewing democracy and confronting autocracy. True, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has made it a priority to reform the multilateral development banks.

But Yellen has also inaugurated a new era of “friendshoring,” or building supply chains with strategic allies. Persaud worries that the doctrine may be an excuse to discipline potential trade partners, and he doubts it will stoke much growth south of Texas. A world in which the U.S. is willing to deny countries market access because they do not align with Washington’s goals, he said, is nothing less than a “new imperialism.”

In recent decades, as the Chinese have expanded their presence in the Caribbean, the U.S. has retreated. The last major agreement was former President Ronald Reagan’s Caribbean Basin Initiative, signed as the United States sought to win favor during the Cold War.

If the pandemic and its aftershocks alerted the United States to the fragility of global supply chains, poor countries also received a brutal reminder of their rank in the global order. Facing vaccine apartheid, many worked together to tackle the health crisis.

On Barbados, the memory of that solidarity is close at hand. Cuba sent dozens of doctors and nurses to Barbados during the COVID-19 pandemic to support a strained health care system. India shipped 100,000 vaccine doses to Barbados, months before the United States did the same.

Mottley delivers a speech during the opening ceremony of the COP26 U.N. Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, Scotland, on Nov. 1, 2021. Yves Herman/Getty Image

When Mottley took the stage at the United Nations’ 2021 climate summit in Glasgow, she addressed central bankers in rich countries. The recovery from 2008, and now the pandemic response, had shown that money is not scarce, she said. Central banks had spent $25 trillion on quantitative easing over the past 13 years. What if they had bought bonds to finance the energy transition?

Mottley called for a multibillion-dollar trust for developing countries to finance green infrastructure. But instead of a low-cost borrowing instrument, philanthropists unveiled a plan at Glasgow that called for international teams to design the energy transitions of poorer countries.

The United States and several European countries announced a “Just Energy Transition Partnership” (JETP) for South Africa, presenting it as the blueprint for similar initiatives in big, middle-income polluting countries. Germany and other leaders of the deal, which have put mounting pressure on emerging markets to retire coal, hoped South Africa would be a relatively easy first case for the JETP model, since it has just one major energy company to overhaul.

The coal juggernaut built up during apartheid has saddled democratic South Africa with a dependency on dirty and increasingly unreliable energy. Eskom, the electricity monopoly, has overseen rolling blackouts for years, which have worsened dramatically in recent months.

South Africa’s JETP is now unraveling. The global energy crisis has made leaders reluctant to shut off power units. Even under more favorable conditions, the transition would be enormously expensive, with an estimated starting cost of $81 billion. The United States, United Kingdom, and European Union jointly pledged $8.5 billion, mostly in loans that will need to be repaid.

Persaud finds the whole arrangement condescending. The conceit of the JETP, he says, is that developing countries lack plans, when what they really lack is capital. The cost of borrowing for clean energy infrastructure in developing countries is around twice that in advanced economies, according to the International Energy Agency. That means the same solar project might be lucrative in Germany, but a money-loser in South Africa.

The higher cost of capital in poorer countries is typically written off as regrettable but rational, since emerging markets are unstable and prone to crisis. But Persaud argues that markets systematically overstate risk, forcing investors to hedge against problems that never materialize.

According to Persaud, at current market rates, investors consistently overpay to hedge foreign exchange risk—the risk associated with fluctuations in currency exchange rates. That premium quickly turns an investible project into an unprofitable one.

In March 2016, for example, the spot price for the Brazilian real averaged 3.91 to the U.S. dollar, and the five-year forward rate was 6.44. (When March 2021 rolled around, the real had fallen less than expected. It was worth 5.64 to the dollar). But back in 2016, to purchase dollars five years out and guarantee against a fall in the real would have cost 11.3 percent per year. If a U.S. investor had evaluated a Brazilian solar project with an annual local currency return of 15 percent, after hedging currency risk to lock in dollar returns, the investor would have been left with a measly rate of just 3.7 percent. Why bother?

To lower the cost of capital for the developing world, Persaud had initially hoped to create a $500 billion trust that would lend to green projects at a set rate. But it ran into opposition, including technical challenges with its proposed use of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), the IMF’s reserve currency. In a new version of the Bridgetown Initiative, Persaud proposes a foreign exchange guarantee specifically targeting this “excess risk premium,” as he calls it.

Hedge funds have long taken advantage of this premium with the carry trade on emerging market currencies, profiting on the perceived risk of emerging markets by borrowing in a low-interest currency, such as the dollar, and investing in higher-yielding debt, such as the Brazilian real. The trade becomes more lucrative right when emerging market currencies depreciate relative to the dollar, bond spreads widen, and poorer governments are starved of capital.

Some economists might wave away the excess risk premium as reasonable compensation for holding risky assets. Others might deny its existence: Why wouldn’t the same investors who want to invest in emerging markets also capture those profits by doing the carry trade themselves? Part of the answer, Persaud thinks, is specialization: Funds that invest in solar or electrical grids are not currency experts, so they are content to keep investing in places where revenues come reliably in euros or yen.

Bridgetown proposes to overcome institutional investors’ aversion to developing countries. With seed capital that he hopes to raise from climate-penitent countries such as the United Arab Emirates, Norway, and Canada, Persaud wants to establish a joint agency with the IMF that would guarantee exchange rates lower than the market-predicted rate of depreciation. He estimates that hedging returns during periods of outflow could add 3.5 percent per year to clean energy projects—enough to attract pension funds and other institutional investors who would not otherwise park their cash in long-term illiquid investments in emerging markets, due to depreciation risk.

“It’s rechanneling this good that would have gone to an investment banker and giving it to an investor in a solar farm,” Persaud said. “Rather than a socially unproductive carry trade, I now have a solar farm.”

International economists including Persaud pose in front of the Élysée Palace in Paris on Jan. 6, 2011, after a working lunch with French President Nicolas Sarkozy to prepare for the G-20 meeting. Lionel Bonaventure/AFP via Getty Images

Will Bridgetown deliver? The crisis response window is shrinking. In the aftermath of the pandemic, the IMF created a new Resilience and Sustainability Trust, and Mottley’s government helped put natural disaster clauses in sovereign bonds. Beyond the foreign exchange guarantee, Bridgetown asks rich governments to provide more capital to the multilateral development banks.

But if the economic shock waves of the past few years initially shook free some international support, they are now triggering protectionist backlash. After approving a new issuance of SDRs in 2021 and facing heat from U.S. Congress members who said that the decision helped adversaries such as China, Yellen has emphasized that there will be no further issuance.

Persaud also has critics who say Bridgetown does too little to patrol Wall Street. The economist Daniela Gabor, who first met Persaud when they campaigned together for the Tobin tax, is conflicted. “He clearly thinks about issues of state capacity; he thinks about reform of the international financial architecture,” she told Foreign Policy, and yet, “the Bridgetown agenda reproduces the political logic of transforming public goods into asset classes for investors.”

Others say lower-rate lending would build public sector muscle in regions where state capacity has been gutted by neoliberalism. “It’s not about, ‘Oh my God, are we going to end up subsidizing the private sector?’ Guess what? We are,” said Anna Gelpern, a professor of international finance at Georgetown Law, on a panel. “It’s about, at any given decision point, is this a good use of your subsidy capital?”

As Mottley heads to Paris next week for the New Global Financing Pact, it is unclear whether she will secure the $100 billion in new capital she is seeking. Persaud said he has made a bid to satisfy “closet protectionists” in the new version of the agenda by adding a sixth plank: a call for reforms to the global trade system.

But American talk of friendshoring puts Caribbean liberals in a bind. Persaud has made a career arguing that international capital flows disfavor developing countries, yet he is alarmed that Barbados’s most powerful neighbor has apparently soured on open trade. In a world of competing blocs, he is not convinced that the nations of the West Indies will fare best sticking with Washington.

Many Caribbean developmentalists share Persaud’s hope of attracting cheaper capital, and his anxieties about a new Cold War. Brian Wynter, the former governor of Jamaica’s central bank who recently led the country through a period of growth and falling unemployment, said he is enthusiastic about the Bridgetown Initiative.

Political stars of the 1970s Non-Aligned Movement had grand plans for self-sufficiency, Wynter said, but tariffs and trade restrictions failed to free the region from the sinews of the financial system. Reflecting on the legacy of Michael Manley, who was Jamaica’s prime minister for most of the 70s and again from 1989-92, Wynter argued that mercantilism is futile.

“You’ve tried to do something on the political stage—the way the world says it’s organized, into nation-states—but it doesn’t have any power,” he said. “These economic realities are not going to change because you’re sovereign and you say waves don’t come in. They’re just going to roll in.”