In 1991, Belarus did not join the Baltic states in striking out independently from the Soviet Union. Now the jury is in.

Independence from the collapsing Soviet Union in 1991 offered its successor states the chance for fundamental reforms. They used these opportunities in strikingly different ways.

Lithuania, as with the other Baltic states, broke away from the old system as quickly as possible. Belarus, remaining under autocratic rule, remained closely tied to Russia.

At first, the Belarusian model of ‘state capitalism’ seemed to work but around 2012 things began to deteriorate. Having spurned the ‘European perspective’ adopted by Lithuania, the associated absence in Belarus of democracy, institutional reforms, good governance and, of course, integration into the European Union now do not bode well for its economic and political future.

Radically different paths

Become part of our Community of Thought Leaders

Get fresh perspectives delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for our newsletter to receive thought-provoking opinion articles and expert analysis on the most pressing political, economic and social issues of our time. Join our community of engaged readers and be a part of the conversation.

Following the example of Estonia, Lithuania was an early and radical reformer. It rushed toward integration into the EU and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in 2004, adopted the euro in 2015 and has become one of the best-performing countries in central and eastern Europe (CEE).

In contrast, Belarus, after timidly implementing some reforms in the first few years of independence, has remained stuck since 1994, when Alyaksandr Lukashenka was elected president. Its state-capitalist model has been based on an implicit social contract: the authorities guaranteed law and order, employment opportunities and a low dispersion of income, while the public sacrificed political freedom. Evidently, this contract broke down in the last few years—decisively so after the rigged elections of August 2020, followed by mounting suppression after the second Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

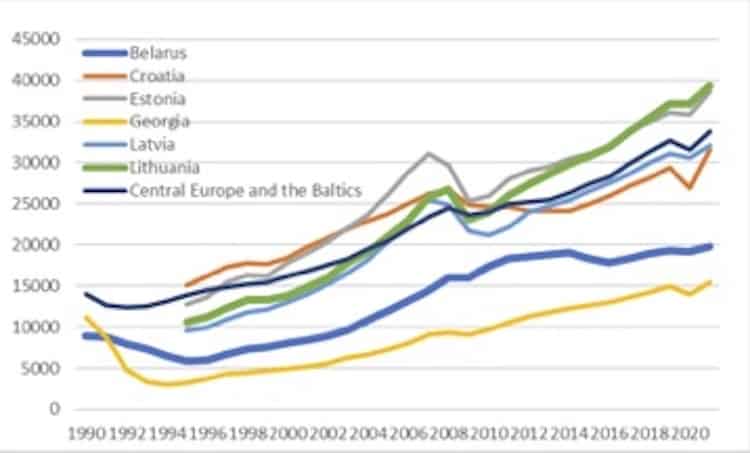

The economic corollaries of this are shown in Figure 1. Having reversed the initial decline in output at the start of the transition from plan to market, the economies of Lithuania and Belarus grew broadly in tandem from 1995 in terms of gross domestic product per head. The data do have to be taken with a pinch of salt, however: Belarus benefited from implicit energy subsidies from Russia which averaged a whopping 18 per cent of GDP during 2001-08 and many prices remain controlled. Lithuania lost about a quarter of her population to emigration in the past 25 years but did perform better, on a per capita basis, especially after 2012.

Figure 1: per capita GDP, 1990-2021 (constant international 2017 dollars at purchasing-power parities)

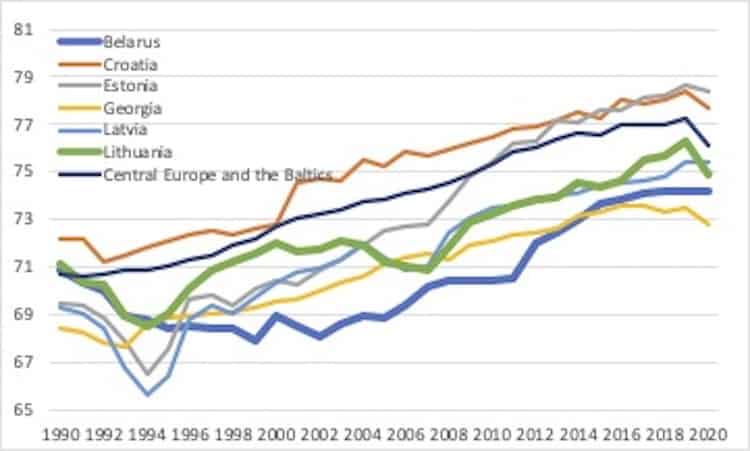

The story is similar when it comes to the fundamental social indicator of life expectancy (Figure 2). Lithuanians have lived longer than Belarussians since 1995. After 1990, life expectancy in Belarus fell by three years compared with a little more than two in Lithuania, where the reversal began in 1994 but in Belarus was delayed until 2002. True, in 2020, the life-expectancy deficit which had opened up between Belarus and other CEE states, bar Georgia, was reduced because the country attracts few tourists, so limiting contagion from the coronavirus (for which Lukashenka advocated driving tractors and drinking vodka as remedies).

Figure 2: life expectancy 1990-2020 (years)

Investment quality

Why is GDP per person so much higher in Lithuania than in Belarus and why has the income differential continued to grow in Lithuania’s favour? To answer that question, we have compared the evolution of standard determinants of growth in the two countries since independence.

Investment is a key determinant. Both countries saw a surge of gross investment in machinery and equipment from around 2000, later reversed, leaving the investment ratio essentially unchanged from the mid-to-late 1990s until 2021. Belarus did though invest about 30 per cent of its GDP on average during 1990-2021, compared with 21 per cent in Lithuania.

Official investment data do not however distinguish quantity from quality. One may doubt its quality in Belarus where investment decisions, in Soviet fashion, have been motivated more by politics than return and the state owns two-thirds of the banking system. Thus, preferential credits have been extended to state-owned enterprises and agriculture.

The booming information-technology industry has been fully competitive in world markets, as have refined oil products and fertilisers, though Belarus has long received ‘loyalty’ rents from Russia. Recently, many foreign IT firms have left the country and the ‘loyalty’ rents have declined, while sanctions have been placed on Belarus’ exports.

Support Progressive Ideas: Become a Social Europe Member!

Support independent publishing and progressive ideas by becoming a Social Europe member for less than 5 Euro per month. You can help us create more high-quality articles, podcasts and videos that challenge conventional thinking and foster a more informed and democratic society. Join us in our mission – your support makes all the difference!

Net foreign direct investment in Lithuania amounted to nearly 4 per cent of GDP on average in 1990-2021, compared with 2 per cent in Belarus. Again, quality matters and the benefits of EU and NATO membership clearly show. FDI in Belarus is heavily tilted toward Russia, which accounts for around 80 per cent of its total (2016 figure), while most FDI in Lithuania stems from the EU.

Market integration

The second key determinant of growth is trade. Exports of goods and services from Lithuania amounted to 58 per cent of GDP on average in 1990-2021—a bit less than the 61 per cent in Belarus. But, while the Belarusian export ratio has held steady since the mid-1990s and maintained its eastward orientation, the Lithuanian ratio shot up from 40 per cent to 80 per cent, reflecting its integration into western markets and participation in the EU single market; Belarus, like Russia, retains a rather restrictive import regime.

Turning to education, our third determinant, Belarus has maintained the good sides of Soviet education, especially in mathematics and science, but remains poor in languages. In both countries, nearly all youngsters attend secondary school, but Belarus has lagged behind Lithuania in recent years. Reflecting the success of the IT industry, Belarus has though recently caught up with Lithuania in individual use of the internet.

It is in the area of democratic rule and good governance that we find the starkest differences—and in Belarus the political and institutional situation is turning from bad to worse. Lithuania has been an unfettered democracy since the early 1990s, consistently scoring top grades in international comparisons: Freedom House awards Lithuania a democracy score of 90 out of 100, while Belarus was demoted from 15 in 2015 to just 11 in 2021.

The distribution of income is less equal in Lithuania than in most advanced economies. As social cohesion is good for growth, Belarus’ low Gini coefficient of inequality may have contributed to growth in the past. More recently though, especially since 2020, social cohesion has all but disappeared.

Accounting for growth

Is growth more driven by crude capital accumulation or more efficient use of existing capital and other resources? The latter include ‘human’ and ‘social’ capital accumulated through education, good governance, efficient organisation, strong institutions and so on. In earlier comparative studies of Estonia and Georgia and Croatia and Latvia, we quantified the relative contributions of different growth determinants to income gaps using a simple growth-accounting model.

When it comes to Lithuania and Belarus, overall efficiency and education again outweigh investment as explanations for the income differential in 2019. Intensive growth is what counts.

Belarus and Lithuania adopted different transition models and reaped different political and economic outcomes. Lithuania was a frontrunner in transition while Belarus started late and its unique, state-capitalist model quickly stalled.

From 1995 to 2021 the income gap between the two countries rose from 83 per cent to twofold in Lithuania’s favour with adjustment for purchasing-power parities and from 58 per cent to more than threefold without it. The latter may be a more appropriate yardstick, in view of the extensive price controls and distortions in Belarus.

Lithuania has outperformed Belarus in most respects, even though Belarus has since 1991 invested 50 per cent more than Lithuania in machinery and equipment relative to GDP and had a more equal income distribution. Lithuania has invested more in human capital and has had more external trade—and, importantly, more democracy, less corruption and better governance.

‘Soft’ factors, such as institutions, governance and education, have prevailed in shaping relative economic performance. Belarus missed an opportunity to boost economic efficiency (‘total factor productivity’) and thus provide a basis for rapid long-run growth. In light of increasing oppression, sanctions and the flight of human capital, its future appears bleak.