By David Wilcock, Deputy Political Editor For Mailonline

11:05 27 Apr 2023, updated 11:05 27 Apr 2023

- IPPR blamed poor health for more than 1.5m people quitting work in five years

- More pronounced among lower earners and women, especially during pandemic

Hundreds of thousands of people being signed off on long-term sick leave are costing the economy an eye-watering £43billion a year, a think tank warned today.

The Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) called for ministers to treat the crisis in the same way that their Victorian counterparts treated public health 150 years ago.

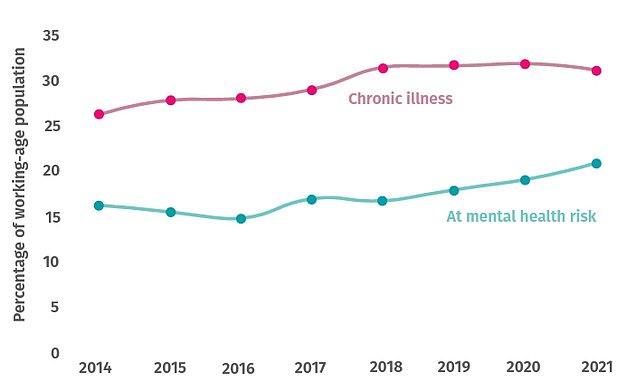

The IPPR estimated that poor health was associated with more than half of the 3.3 million exits from paid employment in the five years running up to the pandemic, and was more pronounced among lower earners and women, particularly during the pandemic.

The UK is getting poorer and sicker, according to the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) which estimated that in 2021 lost earnings linked to long-term sickness cost the equivalent of 2 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP).

Former chief medical officer for England Professor Dame Sally Davies, the chairwoman of the IPPR’s commission on health and prosperity, called for a radical shift in ambition akin to that of the ‘Victorian efforts to transform sanitation and clear slums’.

Dame Sally said: ‘We now know that the UK does worse on health than most other comparable countries – and that this has a tremendous human and economic cost.

‘We also know exactly what policies and innovations could transform health. So it is mystifying why UK politicians, across all parties, have failed to take decisive action.

‘We need a radical increase in our national ambition – equivalent to the Victorian efforts to transform sanitation and clear slums. Why shouldn’t Britain be the healthiest country in the world?’

The think tank commission said that good health is not only vital for people to live enjoyable lives, but that it is also ‘a crucial determinant of our economic prospects, both at an individual and a national level’.

The IPPR estimated that poor health was associated with more than half of the 3.3 million exits from paid employment in the five years running up to the pandemic, and was more pronounced among lower earners and women, particularly during the pandemic.

It added that this pattern suggests the impact of long-term illness on the labour market is not unique to the period since the pandemic and that explanations for current labour market challenges should not solely rest on early retirement – something the Government has been vocal about, including announcing measures to encourage retirees back into the workplace in the spring budget.

The think tank said that experiencing a physical health condition, mental illness, or long-term physical illness of another household member were all associated with a drop in annual earnings of at least £1,200.

Better health could also help tackle the links between health inequalities and economic disadvantage, the IPPR said.

It suggested that a 10 percentage point reduction in the incidence of illness across the UK population would see people on the lowest incomes enjoying the sharpest proportionate increase in income, while women’s earnings would rise at twice the rate of men’s.

It said people from Bangladeshi or Pakistani backgrounds would see the largest average increase in income – worth 2.1 per cent of current income per person in this group, on average.

People in Wales would experience the highest rise in average earnings, worth around 1.8 per cent, and those in the West Midlands and North East would also see average earnings per person increase by around 1.7 per cent, the IPPR said.

It said the UK could become healthier and, therefore, more prosperous through more prevention, better treatment, faster access to care and more effective employment support services and workplace interventions for those with existing long-term conditions, mental health problems or other impairments.

The biggest barrier is not a lack of policy or innovation but rather a ‘lack of capacity across Government to make or sustain positive change’, the think tank said.

A new Health and Prosperity Act – modelled on the Climate Change Act – could ‘hardwire health across all we do’, the IPPR said, explaining that the single piece of primary legislation should consist of commitments including making the UK the healthiest country in the world by the end of a set 30-year period and increasing healthy life expectancy to at least the UK state retirement age across all regions.

Other features should include a new legislative body called the Committee on Health and Prosperity, modelled on the Climate Change Committee, and a health creation fund and health investment bank, the think tank said.

A Government spokesman said: ‘We are committed to levelling up the health of the nation through significant public health investment so everyone can live longer, healthier lives.

‘The measures announced in the Spring Budget include new support to help hundreds of thousands more disabled people and people with health conditions start, stay and progress in work through Universal Support and the Workwell Partnerships Programme, as well as additional work coach time.

‘Our longer term ambition in the Health and Disability White Paper is to shift the focus to what people can do rather than what they can’t, unlocking the opportunity of work and economic prospects for everyone, regardless of their health or disability.’