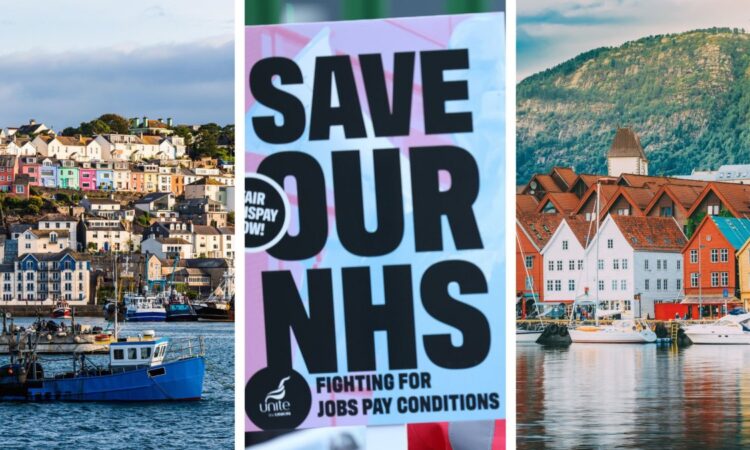

The NHS will be 75 years old in July. Will junior doctors in England still be on strike come the day of that big anniversary?

After members of the Royal College of Nursing rejected a proposed pay deal, and with the British Medical Association still looking no closer to securing an agreement for junior doctors, it feels worryingly possible that walkouts will continue into the summer – prompting further concerns about the ramifications on patient care and growing waiting lists.

But the truth is that even if breakthroughs on staff salaries are suddenly secured, multiple deep-set problems in the NHS will still exist. Unfilled vacancies, overcrowded A&Es, ambulance delays and slow discharging to underfunded social care and community nurses will continue to threaten the public – not just in England but in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland too.

Should the entire “universal healthcare” model of the NHS come under question as it turns 75? Or are there lessons from overseas that we ought to absorb, showing that it can still work if only we make necessary investments and reforms?

Norway is commonly regarded as having one of the best healthcare services in the world. It came top of a study by the Commonwealth Fund, a US think-tank, which compared 11 nations in 2021.

In February, Norway was ranked as the healthiest European nation in a worldwide assessment by the London-based Legatum Institute, coming seventh overall. The UK was 34th, behind the likes of Slovenia, Costa Rica and Thailand.

Like the NHS, Norway provides universal coverage. In fact, it was inspired by the British model, after plans in the 1942 Beveridge Report impressed Norway’s exiled government during the Second World War.

You probably won’t be surprised by the first crucial difference today. Norway spends significantly more on healthcare than the UK each year – the equivalent of £4,596 per person, compared to £2,989 here, according to a 2019 study by the Office for National Statistics.

Perhaps this is to be expected given our economies – Norway’s GDP per capita in 2021 was $89,154 (£71,800), according to the World Bank, vastly more than the UK’s $46,510 (£37,470) .

But it’s not just Norway that we lag behind. “Health spending in the UK was around 20 per cent lower per person than in similar European countries between 2010 and 2019,” a report by the King’s Fund think-tank highlighted last week.

Naturally, high standards are expected from high expenditure. “In Norway, the Patients’ Rights Act specifies a right to receive care within specific timeframes and with maximum wait times applying to covered services, including general practitioner visits, hospital care, mental health care, and substance use treatment,” says the Commonwealth Fund.

Norway ensures “timely availability to care by phone on nights and weekends”, adds the think-tank, “with in-person follow-up at home as needed”. Use of “web-based portals for communicating medical concerns and refilling medications” is also common.

“Norway has fewer doctors per person than the UK, yet it has a lower mortality rate,” according to organisers of the Health in Norway student exchange programme.

They recommend the UK should invest more in technology and mental health services, and take note of how Norway “emphasises prevention before problems arise and maintaining people’s health, rather than curing them after they are sick or injured”.

Sarah Reed, a senior fellow at the Nuffield Trust think-tank, cautions against “over-simplified conclusions” which can lead to “dangerous or politicised solutions”, if we do not take into account differences in economies, lifestyles and geography. Nevertheless, “there’s a lot of valuable learning that can come from other health systems”.

“A lot of the problems in the NHS have built up over time. They connect to a fundamental lack of long-term planning and investment, which is not the case in other health systems, including Norway,” Reed tells i.

“Over the last decade, the UK government has had a real tendency to cut back on investing in buildings and equipment. It’s common in the NHS to have old, cramped buildings with unsafe roofs… We have a maintenance backlog of about £10bn now, while other countries have embarked on hospital modernisation programmes.

“This means that the NHS has much less to work with than other countries that have a similar level of spending overall. We’re a really notable outlier – if you look at Norway and other Scandinavian counterparts, they have invested much more consistently.

“In England, we have fewer CT and MRI scanners per person than Norway or other countries do. That’s important if we’re going to provide timely and responsive cancer care.”

None of these lessons are “rocket science” and many have been “staring us in the face all along,” says Reed.

“When I look at international comparisons, it’s not to find some shiny innovation we haven’t thought of. It’s to see how other health systems get the basics right in ways that maybe we don’t,” she says. “But they’re hard to deliver because of the politics around them and different trade-offs we need to make.”

One thing that’s clear, she adds, is that our payment model is not inherently flawed. “If you look at other successful health systems, including Norway, a lot of them are tax-funded and universal at the point of use like the NHS, and they don’t have the same challenges.”

Shifting to a different approach, such as an insurance-based health system, “would be enormously complicated, disruptive and expensive to deliver and it would probably not fix the deep-rooted problems, which come down to just not having enough capacity to meet demand”.

Another key observation is that a lot of the best healthcare systems are less centralised.

“The NHS in England is a bit unique in running a single health service for the entire population from the centre, which is enormously hard given the size of the country and the population,” says Reed. “Most other health systems give a lot more genuine control to local levels… to have ownership over how healthcare is organised and delivered for their communities.”

Some countries that do have centralised systems have much smaller populations, meaning they’re actually more comparable to the nine English regions, thus providing arguments in favour of decentralisation. Norway, for example, has just 5.5 million citizens, a tenth of England’s population.

This is far from a panacea, however: Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have far fewer patients to treat but are still experiencing many of the same problems as England.

Besides lessons from abroad, perhaps politicians and NHS leaders should also pay more attention to a local success at home. Last week’s report by the King’s Fund, for example, cites Torbay in Devon as a sign that “strengthening community services should be a priority”.

Its author, Professor Sir Chris Ham, explains how in the first decade of this century, “NHS and council leaders in the area chose to increase the provision of intermediate care to be able to respond rapidly to older people requiring care and support at times of crisis. They were able to do so because of a commitment to pool NHS and social care budgets and the ability to use what were nominally NHS funds to provide more social care”.

A study in 2011 showed that these changes “led to reductions in the use of hospital beds by older people and in delayed transfers of care from hospital,” he writes. The story of this seaside resort “reinforces the case for investing in alternatives to hospitals,” showing the advantages of “increased staffing in occupational and physiotherapy, community nursing and social care”.

As for the strikes, it is interesting to hear from Reed that workforce problems are common around the world at the moment.

“Most health systems, even those that are better staffed and funded than ours is, are struggling to recruit and retain staff,” she says. “Issues like unfilled vacancies and increasing levels of burnout are common. But in other health countries, the challenges might not be as severe as it is here.”

Countries like Belgium, Australia and the Netherlands, which have all made better long-term plans on how many medics they will need to serve populations rising both in numbers and age, “have still had challenges in actually recruiting the staff”, she says.

This isn’t very reassuring, however, because “worryingly the NHS is competing for staff in a global market where everyone needs more”. If more staff choose to leave the UK to work abroad, we’re in trouble.

Whether we’re looking at Norway or Torbay, it doesn’t take long to see where healthcare in the England – and around the rest of the UK – is going wrong and how politicians could help the NHS. So much of it, however, comes down to what we’re willing or able to pay.

Twitter: @robhastings