Picture the setting: Bill Clinton has been US president for just over a week, jeans are worn baggy and Whitney Houston is topping the charts with I Will Always Love You.

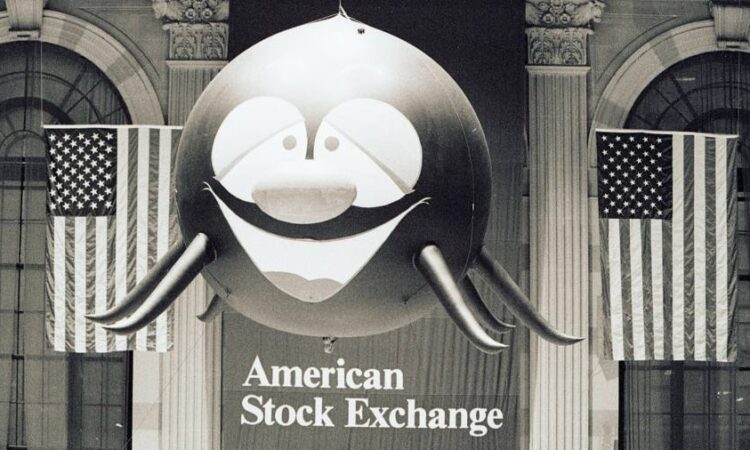

The year is 1993 and a big change in financial markets and fund management is being launched with the hoisting of a giant inflatable spider over the trading floor of the American Stock Exchange in downtown Manhattan.

The stunt was to mark the debut 30 years ago of State Street Global Advisors’ S&P 500 Depository Receipt, or SPDR, on January 29 1993. It was not the first exchange traded fund — there was a Canadian one launched on the Toronto Stock Exchange in 1990. But it was SPDR that sparked the development of the huge ETF industry and led the way since.

The web of US-listed ETFs is now worth $6.5tn, according to SSGA. That’s roughly two-thirds of the global total. And SSGA’s initial fund is still the biggest, at $355bn. Activity in SPY — its ticker — is even more impressive: an average $39bn in trades daily and towards the end of last year, its volume was almost three times that of mighty Apple. Put another way, more than half of all S&P 500 constituents are each worth less than the volume of SPY trading on a typical day. A SSGA survey found 40 per cent of investors say they own an ETF in their portfolio.

SPDR remained a financial minnow for years after the launch compared with the size of the mutual fund universe. Mutual funds were then — and still are — the behemoth of the investing industry. But SPDR and ETFs offered something different. Back in 1993, the Boston Herald described the new product as “part stock, part mutual fund, part index product, part S&P 500”.

Being exchange-traded, they allow investors to buy and sell units during the trading day, while their rivals offered one single price after each day’s close. The upstarts also charge a fraction of the fees demanded by mutuals and incur fewer taxes, too.

It took time for these tax advantages to draw in the frequent traders for whom they’re most useful — and for professional investors to realise ETFs could work for them as trading and hedging tools as well as being the cheap investment vehicle for mom-and-pop investors that they were conceived as. But the industry has since grown like topsy.

One reason for that is the ability of fund providers to innovate, launching a myriad of ETFs allowing investors to gain exposure to an array of assets, including commodities and corporate bonds. There are even ETFs designed for use as short-term trading tools offering extra leverage for positive and negative bets.

For those in the industry, the sky remains the limit. At an event to mark the 1993 anniversary last week, Sue Thompson, SSGA’s head of distribution for SPDR exchange traded funds in the Americas, suggested a private equity ETF could eventually be created. “Remember that ‘it can’t be done’ was what people thought about ETFs for gold and for high-yield bonds,” she said.

The industry is also enjoying another trend that vindicates its success: a rising number of mutual funds are being converted into ETFs.

Some 35 funds, worth a combined $55bn, have made the switch in the past two years, according to Morningstar. The conversions follow a rule change from the Securities and Exchange Commission in 2020 that lowered the costs and eased the difficulties of the move.

Californian boutique Guinness Atkinson was the first in March 2021 and bigger names have followed, including funds offered by the likes of JPMorgan, Neuberger Berman and Franklin Templeton. Mutual fund titan Fidelity is in the process of converting six funds.

“It seems like I get asked about the concept of conversion at least once a week every week now, compared with once a month not so long ago,” said Richard Kerr, partner and funds specialist at law firm K&L Gates.

Despite the success of ETFs and the recent conversions, they still trail the US mutual fund universe in size. Mutual funds managed some $27tn of assets at the end of 2021, according to industry body Investment Company Institute. However, ETFs are faster-growing.

Take equity ones. Net inflows into these have contrasted with outflows from their mutual fund rivals each year since 2006, according to Bank of America research. Inflows of more than $500bn last year in the US were the second-best on record, in spite of the S&P 500 suffering its worst year since 2008, losing 19 per cent.

At last year’s relative growth rate, equity ETFs could overtake mutual funds by 2036, BofA believes. A sharp speeding-up of conversions could change that pace. The latest trend of mutual fund switching only amplifies how far the upstarts have come.