Regulators’ attitudes toward bank M&A have put many would-be buyers and sellers on the sidelines, and some industry experts believe that is hindering competition and only benefiting the largest banks that already dominate market share.

Prolonged closing timelines as a result of stricter deal review by regulatory agencies have stifled regional and superregional banks’ M&A appetite. As a result, only three U.S. bank megadeals — a deal with a value above $500 million at announcement — were announced in 2022, compared to 23 such deals in 2021.

For example, PNC Financial Services Group Inc. is open to striking another transformational deal like its June 2021 acquisition of BBVA USA Bancshares Inc., but the company is holding off from future deals because, “I don’t think regulators would be open to us,” Chairman, President and CEO William Demchak said during an industry conference last month.

“I think there’s a bunch of financially attractive deals that everybody would love. I just don’t think they’ll ever get approved,” Demchak said. “To go through the effort for a smaller deal and just be hung up with one-year, years-plus approvals with no rules, I think we have to wait.”

The CEO predicted that if the current regulatory environment, during which the pace of M&A has slowed dramatically, persists, only a few banks will control the entire U.S. deposit base.

“If they don’t change what’s happening here, and they basically say, ‘We want no more mergers,’ I mean you’re going to have two or three banks control the entire deposit base in this country and that can’t be the desired outcome of our government or our regulators,” Demchak said. “That’s what’s going to happen short of them opening up the ability to do M&A.”

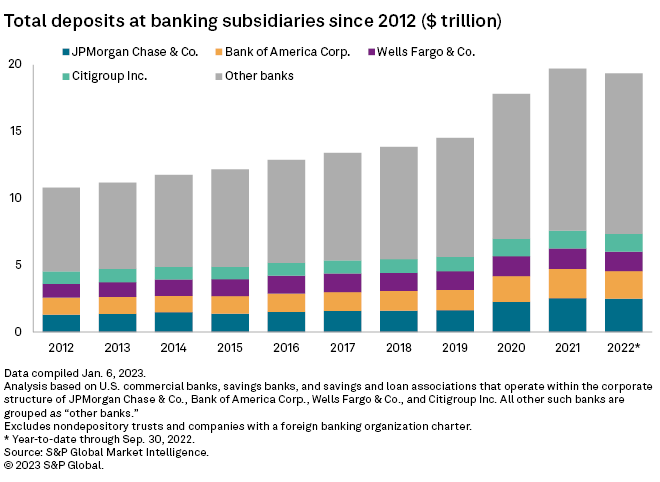

Year-to-date through Sept. 30, 2022, the Big Four U.S. banks, JPMorgan Chase & Co., Bank of America Corp., Citigroup Inc. and Wells Fargo & Co., held 38%, or more than one-third, of total deposits among all U.S. banks, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data.

Like Demchak, some experts believe the largest U.S. banks will only gain market share as a result of regulators’ attitudes toward M&A.

“The longer bank M&A faces increased scrutiny, the more we think this benefits the larger banks as they continue to gain market share,” Barclays analyst Jason Goldberg wrote in a Jan. 3 note.

Benefiting the biggest

It is largely believed that regulators are taking a harder look at deals resulting in a bank with more than $100 billion in total assets. But in doing so, regulators are suppressing regional and superregional banks’ M&A appetite, making it harder for them to pair up and compete with the most dominant players, industry experts said.

“By allowing the superregionals to get bigger — yes, you’ve got more concentration, but you also have more competition for the giants, and that’s a good thing,” said James Angel, associate professor at Georgetown University’s McDonough School of Business, whose specialties include financial market regulation.

In many cases, superregional banks are looking to expand their footprints nationally through M&A to better compete with the largest banks that already have nationwide footprints. For example, PNC’s recent acquisition of BBVA USA expanded the bank’s footprint west into states including Texas, California and Colorado.

“For PNC to buy another regional bank in a place where they have no footprint, basically is not going to decrease competition in that area,” Angel said in an interview. “Instead what it means is that PNC is going to gain economies of scale, and it means they can serve that area more efficiently and be more competitive in that particular area.”

“It’s not just about getting big to compete with Chase and Citi,” for example, but it can also bring “competitive advantages and shake up that market that may have been sleepy or underserved,” he added.

Regulators are not obstructing competition

Other industry observers argue that regulators are not hindering competition.

“I don’t think the regulators are trying to be anti-competitive or anything of that nature,” Christopher Marinac, director of research at Janney Montgomery Scott LLC, said in an interview. “I don’t think that competition is an issue.”

Marinac argued there is still adequate competition to create choices for customers. Further, regulators are likely in favor of banks combining in M&A because having fewer banks makes regulating the industry easier, he added.

The prolongment of deal closing periods is more a function of regulators focusing on protecting consumers and not a result of wanting to stifle competition, said Rutger van Faassen, head of market strategy at Curinos.

“The pendulum swings back and forth as there’s different power in Washington,” van Faassen said. “In banking, we just have seen that it’s taking longer to get the approval, but there haven’t been clear cases yet where they say, ‘No this is not allowed, and this is all because it’s hurting competition.'”

Though the pace of M&A has slowed and transactions are taking longer to close, deals are still getting done, allowing smaller banks to pair up to gain scale and better compete, experts said.

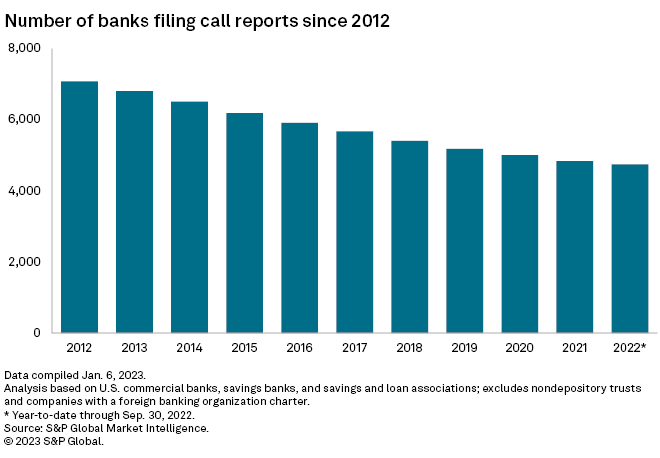

The number of banks has continued to decline over the past decade as depositories pair up. Through Sept. 30, 2022, there were 4,744 commercial banks, savings banks and savings and loan associations operating in the U.S., down from 7,077 one decade ago in 2012.

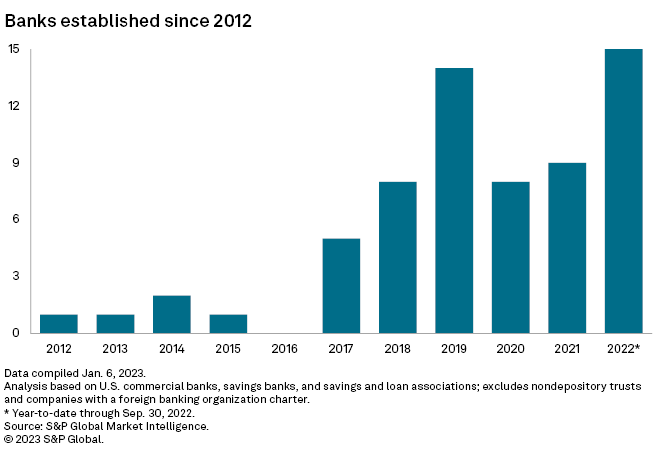

In comparison, there have not been very many new banks created. In 2022, there were 15 new banks established, which was the most in a single year over the past decade.

Still, the U.S. is rife with competition among depositories, unlike the banking oligopoly in Canada, which is largely dominated by six banks.

“Look, we’re nowhere near that in the U.S.,” van Faassen said.