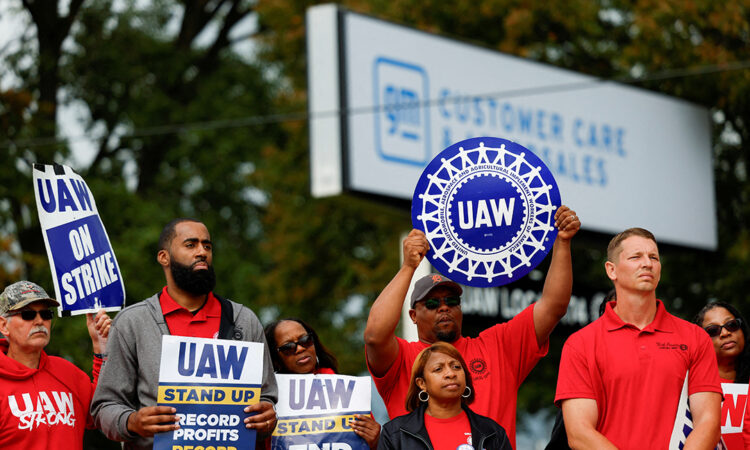

In 2023, the United States saw the strongest wave of labor unrest in decades. Punctuated by high-profile auto worker and actors’ union strikes, some analysts see this uptick in organized labor activity signaling a revival in worker power after a long period of declining union membership and stagnating wage growth. However, others warn that increased work stoppages could threaten U.S. supply chain resilience and economic competitiveness.

What happened last year?

More From Our Experts

There were thirty-three major work stoppages in 2023, the highest number in twenty-three years. (Major work stoppages are defined by the Bureau of Labor Statistics as involving one thousand or more workers and lasting at least one shift.) Almost five hundred thousand workers were involved in stoppages last year—the second-most since 1986—and a 280 percent increase from the previous year. The stoppages added up to almost seventeen million “days idled,” the most since 2000.

What’s behind the surge?

More on:

Experts sympathetic to labor argue it is the result of longstanding worker unhappiness. They point out that well-paying and stable unionized manufacturing jobs have increasingly been replaced by low-skill, low-wage “gig economy” work that comes with fewer, if any, worker protections, as well as by higher-tech jobs that these workers are not trained to do. Since the 1970s, real wage growth for lower- and middle-income workers has stagnated, and income and wealth inequality has risen.

At the same time, historically tight labor markets in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic have strengthened workers’ bargaining power. Several major union worker contracts also happened to be up for renewal in 2023, creating the conditions for major strikes—especially since polls show public support for unions hit a fifty-seven-year high of 71 percent in 2022.

Striking workers could also have been incentivized by support from President Joe Biden, who became the first sitting president to join a picket line when he joined the striking United Auto Workers last year. His administration’s signature legislative accomplishments—the Inflation Reduction Act, CHIPS and Science Act, and the Infrastructure and Jobs Act (IIJA)—each contain provisions promoting and upholding workers’ rights. During his presidency, several federal agencies, including the National Labor Relations Board, the Department of Labor, and the Federal Trade Commission, have made labor-friendly rule changes. These include limiting the scope of workers classified as “independent contractors,” increasing eligibility for overtime pay, and banning most worker non-compete agreements.

More From Our Experts

Is U.S.-based manufacturing good for the economy?

During the 1950s heyday of American manufacturing, one in three U.S. jobs were in manufacturing, and one in three workers were unionized. Inequality was low, but goods were expensive relative to today.

During the “Washington Consensus” era of the past four decades, policymakers of both parties prioritized free trade based on a belief that it would make U.S. products more globally competitive. This brought benefits, especially reduced prices for consumer goods. It also brought unionization rates to an all-time low of 10 percent as largely unionized manufacturing jobs moved overseas. Experts now point to the loss of these jobs to import competition—from China in particular—as a driving factor in rising trade skepticism in both major parties. While only 13 percent of labor actions last year were in the manufacturing sector, those jobs are central to recent protectionist policies.

More on:

Policymakers are currently hoping to reverse some of those trends. Democrats and Republicans alike are campaigning on U.S. workers’ job security and wages, which are finally rising after a long period of stagnation for lower- and middle-income earners. Likewise, the decades-long trend of increasing income inequality reversed in 2022, although it is unclear if this will last. The shift is also uncommonly bipartisan: in addition to President Donald Trump initiating the shift in trade policy, Biden’s CHIPS and IIJA legislation passed with Republican support.

However, critics point out the downsides to ostensibly worker-friendly protectionism. Many experts argue that tariffs and other trade barriers reduce efficiency and consumer choice and contribute to inflation, which is still above the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target. Protectionism could also slow the green energy transition by making crucial imported material and technologies more expensive and harming ties with allies, they say.

Could unions influence foreign policy?

The overall economic impact of last year’s strikes was minimal, and U.S. economic growth continued to outpace its peers. However, some massive union contracts, including those for rail and postal workers, are up for renewal in 2024. Given the centrality of rail and postal workers to the country’s economy and supply chains, a strike involving either of them could have major electoral consequences for Biden, as polls indicate voters already broadly disapprove of his handling of the economy.

Unions could also more directly influence foreign policy. Biden, under his “Foreign Policy for the Middle Class” framework, recently announced his opposition to the acquisition of Pittsburgh-based U.S. Steel by the Japanese firm Nippon Steel, a deal opposed by the United Steelworkers Union. Biden has also made creating “good jobs” a pillar of his trade policy, set high labor standards as a condition for any firm hoping to receive the billions of dollars in subsidies in “critical” sectors, and tripled Trump-era tariffs on steel and aluminum while adding many of his own, including a recent tariff on electric vehicles.

Meanwhile, Trump has promised to double down on his union-supported first-term tariff agenda if reelected, including by imposing a 10 percent tariff on all imports, a 60 percent tariff on Chinese imports, and a 100 percent tariff on all cars made outside the United States. He is also backed by a small but growing contingent of Republican Senators hoping to win a bigger share of organized labor, which some analysts say could further shift the policy debate in the next Congress.