G7 leaders are set to reach a political agreement to provide Ukraine with $50 billion of financial aid using the windfall profits generated by frozen Russian central bank assets, according to several people with knowledge of the matter.

Technical details of a deal are still to be finalised after a G-7 leaders’ summit taking place in Italy this week, an Elyseé official confirmed, speaking on condition of anonymity.

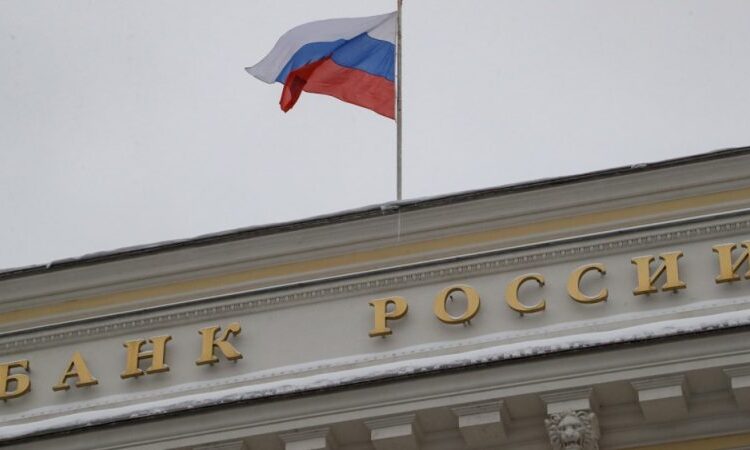

EU member states agreed earlier this year that using the windfall profits generated by the frozen capital is legally sound as the profits, contrary to the capital of the assets, do not legally belong to Russia.

Under the plans, 90% of the funds would initially be allocated to the European Peace Facility (EPF), the bloc’s mechanism to reimburse member states for weapons delivered to Kyiv, and then to the newly created Ukraine Assistance Fund (UAF).

The remaining 10% would be transferred to the EU budget and used to boost the capacity of the Ukrainian defence industry.

However, the new idea at the G7 level is to use this to front-load more, faster help in the form of a massive upfront loan and secure them against political changes in the participating member countries.

Key questions such as who issues the debt and who shares the risk are still being hammered out, the Elyseé official said.

US President Joe Biden, who had been spearheading the plan, is expected to press his G7 counterparts to agree to the innovative plan, but on the eve of the summit, it caused a rift between the US and European governments.

To move ahead with the plan, people familiar with the talks said, there would need to be a need for risk-sharing between the EU and the US, as EU countries and the European Central Bank have been wary of the potential risk to the EU’s single currency.

Eurozone finance ministers gave their political backing last week but said the terms would need to be discussed after the G7 summit gives political guidance.

However, the plan would rely heavily on the fact that Russian frozen assets remain frozen in the long term until Moscow agrees to pay reparations and would require changes to the EU’s Russia sanctions regime to provide for steady rollover.

[Edited by Alice Taylor]