The European Central Bank lowered interest rates on Thursday for the first time in nearly five years, signaling a pivot away from its aggressive policy to stamp out a surge in inflation.

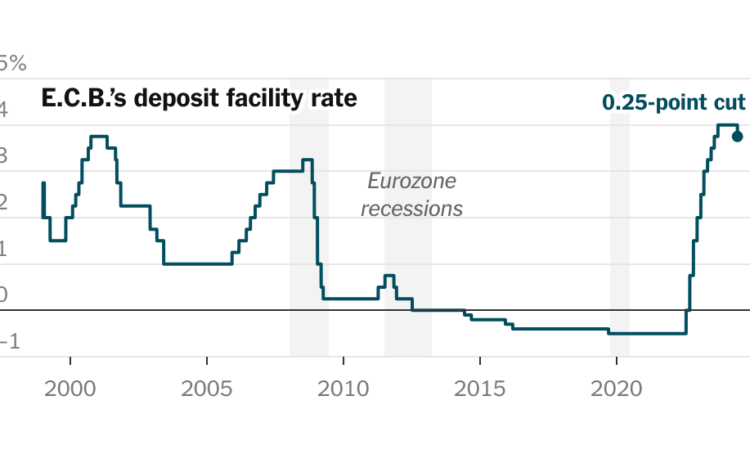

As inflation returned within sight of the bank’s 2 percent target, officials cut by a quarter-point their three key interest rates, which apply across all 20 countries that use the euro. The benchmark deposit rate was lowered to 3.75 percent from 4 percent, the highest in the bank’s 26-year history and where the rate had been set since September.

“The inflation outlook has improved markedly,” Christine Lagarde, the president of the E.C.B., said on Thursday at a news conference in Frankfurt. “It is now appropriate to moderate the degree of monetary policy restriction.”

But she did not give a strong indication of how many more times or how soon the bank might cut rates again.

There is growing evidence around the world that policymakers believe high interest rates have been effective at restraining economies to slow inflation. Now, they are lowering rates, which could provide some relief to businesses and households by making it cheaper to obtain loans.

On Wednesday, the Bank of Canada became the first Group of 7 central bank to cut rates. Central banks in Switzerland and Sweden also cut rates recently.

There is more reluctance to ease policy in the United States, where officials at the Federal Reserve are waiting to be more confident that a recent run of stubborn inflation readings will end. The Bank of England has opened the door for rate cuts, with some officials saying they could come this summer.

The E.C.B.’s rate cut on Thursday, the first since September 2019, sends a strong signal that the worst of Europe’s inflation crisis is firmly in the rearview mirror. In late 2022, average inflation across the eurozone peaked above 10 percent as a surge in energy prices fed through to consumer goods and services, and workers demanded higher wages to blunt the pain of the jump in prices.

In recent years, the E.C.B. embarked on its most aggressive cycle of rate increases. Policymakers lifted the deposit rate, which is what banks receive for depositing money with the central bank overnight, to 4 percent in September, from negative 0.5 percent in July 2022.

That helped bring inflation in the eurozone down to 2.6 percent in May. For most of the past year, lower energy prices have helped pull down inflation. Food inflation has slowed to below 3 percent, from more than 12 percent a year ago.

“Monetary policy has kept financing conditions restrictive,” Ms. Lagarde said. “By dampening demand and keeping inflation expectations well anchored, this has made a major contribution to bringing inflation back down.”

On Thursday, Europe’s benchmark stock index climbed to a record high before the rate cut was announced, but erased some of its gains amid signs that the bank would be cautious about future rate cuts.

The central bank warned that there were still signs of strong price pressures, which would mean inflation would stay above the 2 percent target “well into next year.” The overall inflation rate is forecast to average 2.2 percent next year, above the bank’s projection three months ago.

Recent inflation data was stronger than expected. Services inflation, which has been particularly stubborn, accelerated in May to 4.1 percent, up from 3.7 percent the month before. Policymakers have been keeping a watchful eye on wage growth, which can push up consumer prices if companies pass on higher wage costs rather than absorbing them.

“Wage growth is elevated,” Ms. Lagarde said, though it was forecast to moderate over the course of the year.

She added that she would not describe the central bank as in a “dialing-back phase” yet. Instead, policymakers, using new economic data, will need to “constantly confirm we are on this disinflation path” every time they meet to decide on interest rates.

Traders scaled back their bets on more rate cuts this year, leaving the probability of reductions in September and December at about an even chance.

“This is not a central bank in a rush to ease policy,” Mark Wall, the chief European economist at Deutsche Bank, said in a statement.

Officials are facing a challenging balancing act. On the one hand, policymakers want to cut interest rates in a timely manner to avoid causing excessive damage to the economy, which could push inflation below their target. On the other hand, they do not want to ease policy too soon, which could cause inflationary pressures to revive.

Investors have looked at the United States, where inflation is proving to be stickier than initially expected, and wondered whether Europe should take what’s happening as a warning about what could come next.

There is also skepticism about how far the E.C.B. could cut rates while the Fed waits. Higher interest rates in the United States would continue to tighten financial conditions there and in other countries because of the global role of the dollar, which would in turn weaken the euro and risk importing inflation.

After more than a year of economic stagnation, the region’s economy is showing some signs of recovery, further justifying the E.C.B.’s cautious approach. On Thursday, the bank’s staff forecast that the eurozone economy would grow 0.9 percent this year, from a 0.6 percent forecast three months ago.

The services sector is expanding, the manufacturing sector is stabilizing at subdued levels and exports are expected to grow as global demand increases, Ms. Lagarde said. At the same time, a combination of lower inflation and higher wages will improve consumers’ spending power. Monetary policy will also have less of a drag on the economy as rates decline, she added.

Still, Ms. Lagarde highlighted the uncertainty in the inflation outlook, noting that price growth would fluctuate around its current level for the rest of the year and that there would be “bumps on the road.” And so rate decisions will be decided at each meeting based on incoming data.

“We are not precommitting to a particular rate path,” she said.