It’s natural to worry about how possible regime change in Westminster may affect our investments, but we see four reasons for comfort.

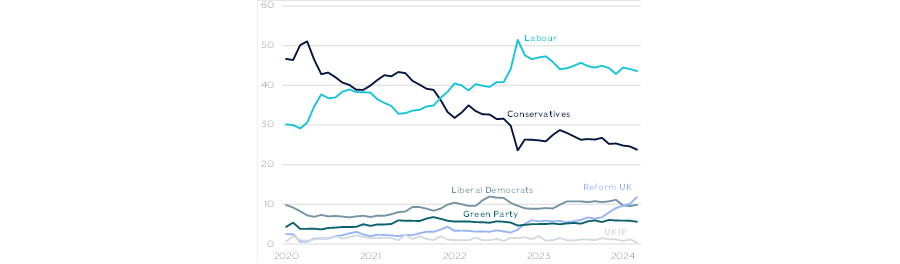

The context of the forthcoming election is that the Conservative Party has a mountain to climb to avoid a heavy defeat. Labour has a large lead in the polls (around 20 percentage points) that has been sustained for more than a year and a half.

The polls can of course be wrong, or shift – but it would take a historic swing in such a short time to make a big difference to the outcome.

UK election opinion polls

Source: Rathbones

It isn’t just the polls suggesting that the Conservatives face an uphill battle, the public rate Labour better than the Conservatives on all three of the issues they care most about – the economy, the NHS and immigration.

Rishi Sunak is personally unpopular too, in contrast to the start of his premiership. His net approval rating is now close to that of Liz Truss at the end of her ill-fated time in Number 10, and far behind that of Keir Starmer.

Local elections earlier this month also saw the Conservatives lose hundreds of councillors, while several recent by-elections have seen swings to Labour well above 20 percentage points.

In other words, the chance of a change in the political landscape, after 14 years of Conservative rule, is high. It’s natural to worry about how possible regime change in Westminster may affect our investments, but we see four reasons for comfort.

No dramatic short-term change in fiscal policy on the cards

Shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves has taken a leaf out of the Blair/Brown 1997 playbook in shadowing a lot of existing economic policy. She has pledged not to raise the most significant taxes – income tax, national insurance, capital gains tax and corporation tax.

And she has committed to follow a set of fiscal rules virtually identical to the current ones (as well as showing her commitment to those rules by ditching previous pledges which don’t comply with them).

This cautious strategy means the election is not likely to alter the short-term path of the economy much, or to upset the gilt market. Labour’s clearest points of difference on fiscal policy are arguably its plan to charge VAT on private school fees and to change the tax treatment of carried interest.

That’s significant for those affected but doesn’t move the needle for the economy. We’d expect it to continue its recovery from the shallow recession of last year.

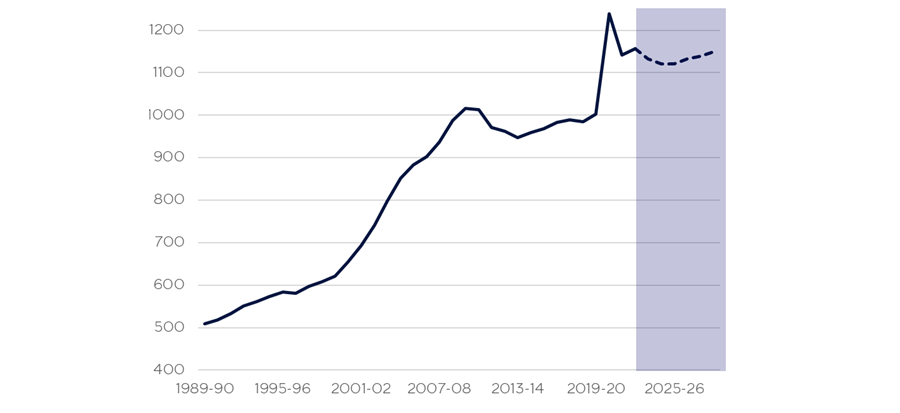

Total managed expenditure

Source: Rathbones

Whichever party wins the next election will eventually have to confront the so-called ‘fiscal fiction’ which underlies current spending plans. This is the assumption that there will be significant spending restraint in key departments, which are likely to prove politically impossible in practice. But that isn’t a Labour-specific issue.

Labour has dropped radicalism of Corbyn era

The past general election in 2019 offered voters two radically different economic visions, Boris Johnson’s pledge to ‘Get Brexit Done’ against Jeremy Corbyn’s socialist agenda.

But the Labour Party has transformed since then, emphasising ‘partnership with business’ and courting the City. There are some key differences between the two parties’ economic policy platforms today, but these are much smaller than in 2019.

Gone is Labour’s commitment to nationalisation. The party does plan to renationalise virtually all passenger rail services within five years, as existing contracts with private operators expire. Yet things have been moving in this direction by stealth anyway.

The current government has already taken over several major rail franchises, including Southeastern, LNER, ScotRail and TransPennine. Labour also plans to establish a publicly owned company to invest in green energy, such as floating offshore wind, but this is no wholesale nationalisation.

New government may have political capital for much-needed reform

Reflecting the long-term poor performance of the UK economy, there are a few key areas which both main parties have identified as ripe for change, but where the current government has failed to muster the political capital to pass any significant reform. A new government with a fresh mandate could make a positive difference.

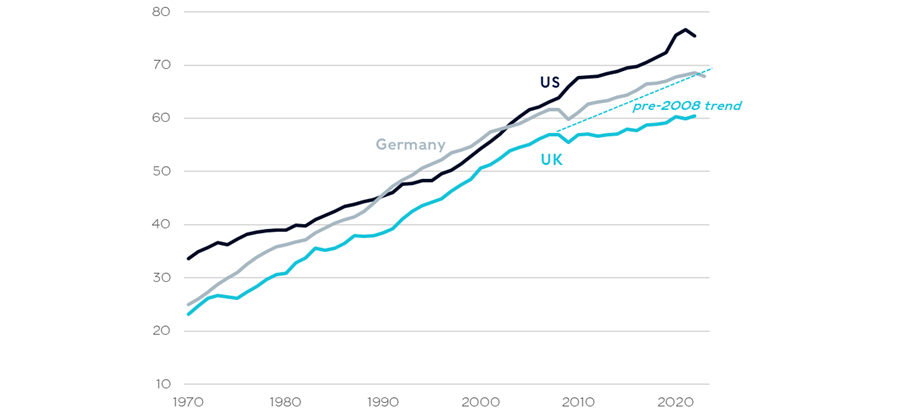

GDP per hour worked in dollars

Source: Rathbones

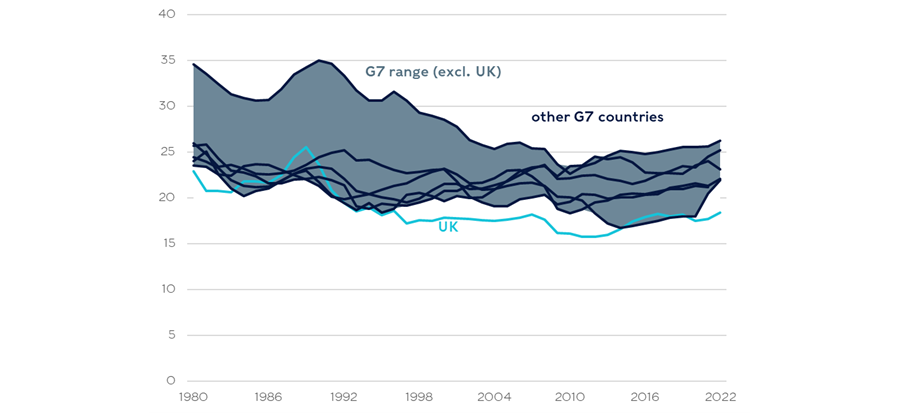

The context behind all of this is the weakness of productivity growth in the UK since the global financial crisis, which in turn is linked to the long-term weakness of investment. (shown in the chart above and below.)

Investment as a percentage of GDP

Source: Rathbones

Many of the specific problems policymakers worry most about – from regional inequality to the state of the health service – are ultimately connected to insufficient investment.

A key issue both parties have identified as a barrier to investment is the UK’s unusual planning system. Our system is discretion-based, whereas virtually every other advanced economy relies more on zoning and rules.

It is slow and unpredictable, discourages development and makes building much-needed infrastructure harder. Infrastructure projects here face much higher costs than other advanced economies, in part because of planning-related delays and legal challenges.

London’s CrossRail, for example, cost 10 times as much per mile as Madrid’s metro system. The spiralling costs of HS2 are notorious, and the project has been the defendant in 45 separate legal cases since 2018.

This would be an appealing area for a new government with a fresh mandate to address, particularly as it can be done without the need for large spending commitments.

Rachel Reeves said, “This Labour Party will put planning reform at the very centre of our economic and political argument.”

There is likely to be a more standardised approach to what is and isn’t allowed. More planners will be hired to reduce backlogs and delays too. So-called ‘grey belt’ land may be targeted for development – things like car parks and wasteland which are currently part of the green belt.

Investors have set the bar for success low

UK assets currently appear cheap compared to their fundamentals on a variety of different measures. International investors fell out of love with UK equities in the period of instability which followed the 2016 Brexit vote. It wasn’t until then that the gap between the valuations of stocks in the UK and elsewhere (particularly the US) emerged.

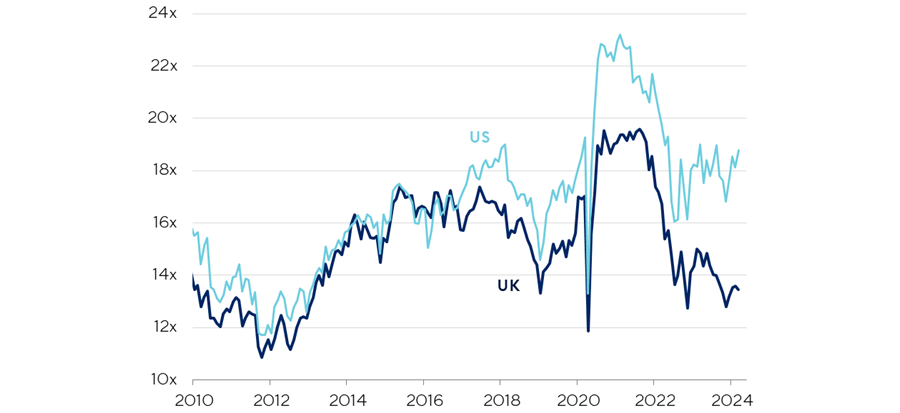

Price-to-earnings ratios, adjusted for sector composition

Source: Rathbones

The gap is much larger than can be explained by the relative growth and quality characteristics of UK firms, or by the sectoral makeup of the UK market. The story is similar when we analyse currencies – sterling trades well below measures of its ‘fair value’ based on economic fundamentals.

Some reasons for international investors’ antipathy towards UK assets could change. Following years of domestic political instability – characterised by a succession of prime ministers and a lack of policy space to address structural issues – the possibility of a new government with a reasonable majority engenders hope.

Stability alone might be an improvement on the political and economic turmoil that has existed since 2016. Investors have set the bar for success for the next administration low.

Oliver Jones is head of asset allocation at Rathbones. The views expressed above should not be taken as investment advice.